Photo courtesy of iStock.com/Thylacine

Professional Engineers Get in Front of Flooding

In June 2013, heavy rainfall triggered catastrophic flooding across southern Alberta, submerging one-quarter of the province and causing 32 states of emergency. Five lives were lost in the disaster that caused $6 billion in financial losses and property damage.

Determined to avoid similar devastation in the future, professional engineers are developing ways to prevent Mother Nature’s rivers and tributaries from overwhelming our communities in the first place.

Developing and improving monitoring techniques

In the civil engineering department at the University of Calgary, professional engineer Mamdouh El-Badry, PhD, is working on improving monitoring techniques so flaws or weaknesses in buildings and bridges can be found and fixed before natural disasters hit.

Dr. Badry says bridges are currently checked visually for potential issues every two years, and buildings every five, but his research may make it possible to increase the frequency and accuracy of these inspections.

“In collaboration with geomatics engineering researchers, we are developing image-based techniques to detect surficial cracks and fractures, determine their width and extent, and investigate their causes and effects,” he explains.

“We are also developing vibration-based techniques that allow us to detect and identify internal and hidden damages and flaws and estimate their severity. This information can help infrastructure owners and managers make decisions on the necessary measures for maintenance and repair.”

Using digital cameras and sensors to detect vibrations and movements, Dr. Badry can remotely track traffic, snow, and spring run-off on bridges. He says his techniques can be developed to be used in different types of structures.

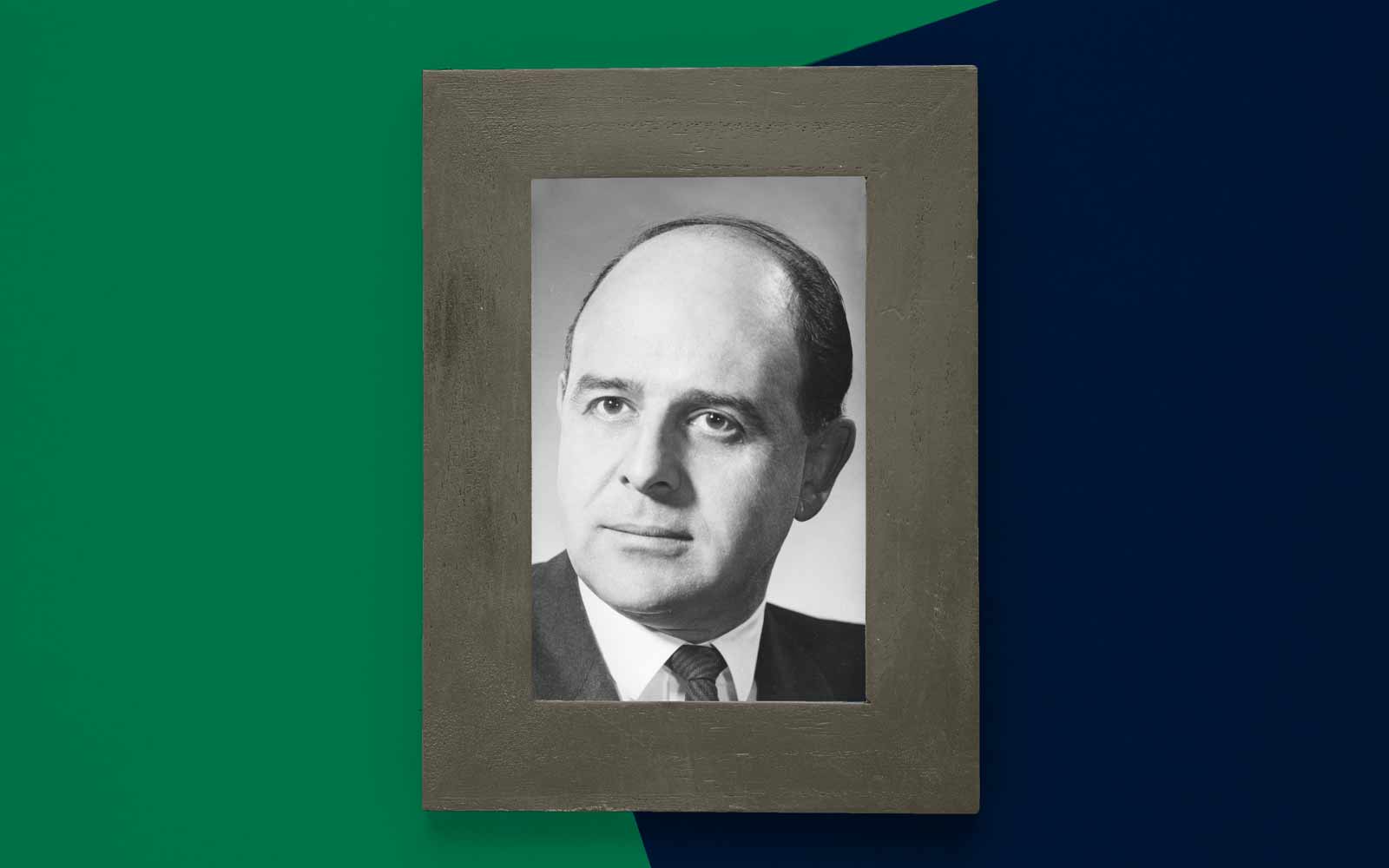

Dr. Mamdouh El-Badry, P.Eng., (right) is developing and improving monitoring techniques that can detect weaknesses in bridges and buildings, enabling the faults to be fixed before natural disasters hit.

Photo courtesy of the University of Calgary

Building the High River floodgate

As part of its ongoing flood-mitigation strategy, the Town of High River made a series of infrastructure improvements to its Centre Street Bridge in 2018, including the installation of a sliding floodgate on the south side of the bridge.

“The town needed something that could be deployed quickly, and some of the more common solutions—such as stop logs—take too long to deploy,” says professional engineer Reiley McKerracher, High River’s director of engineering, planning, and operations. “The gate itself also has redundancy built in. It can deploy through the control panel, but in the event of a power outage, it can be manually deployed as well.”

The track the gate slides on was designed so it can be covered during the winter months—shielding it from grit and allowing for snow plowing—and opened when the gate is in use.

The project wasn’t without its challenges: “The biggest issue was dealing with traffic,” says McKerracher, noting that Centre Street is the main corridor between the north and south parts of High River.

“Most of the work was done with a lane closure and a set of temporary signal lights to control traffic on a short, single-lane portion of the road. There were periods when the road had to be completely shut down, which created even larger traffic-management issues.”

Though the gate hasn’t had to perform in a real-life scenario yet, it’s tested every spring to make sure everything is functioning as it should.

The High River floodgate stretches across the south end of the Centre Street Bridge. If the Bow River floods in the future, as it did in 2013, the gate can be closed to keep the water from reaching the town.

Creating future protection for the Calgary Zoo

The Calgary Zoo was also affected by the 2013 flood, with repairs alone costing $50 million. Once the water receded, the zoo commissioned the creation of a comprehensive flood-mitigation strategy that would protect more than $300 million of infrastructure well into the future.

ISL Engineering and Land Services and Associated Engineering answered the City of Calgary’s call for the design and implementation of the mitigation plan.

Early on, the need for flood protection above and below the ground surface was realized—when the river rises, so does the groundwater. A cofferdam perimeter wall was used to isolate St. George’s Island, the Bow River site of most of the zoo, and was combined with a dewatering system to manage stormwater runoff and groundwater levels.

ISL and Associated used hydrogeological modelling to select the appropriate dewatering system—one that was simple, reliable, and cost efficient. The flood model was refined and calibrated with the performance data gathered, and final tests confirmed that one-in-100-year flood protection had been accomplished.

After the project’s completion, the Calgary Zoo logged what it called its best year ever, in 2018. The zoo will continue its work—safe and without fear of flood— as a leader in wildlife conservation.

After the 2013 flood cost the Calgary Zoo $50 million in repairs alone, the zoo commissioned the planning and creation of a flood-mitigation strategy that would provide protection for years to come.

The Town of High Level was devastated by the 2013 flood. Learn about the town’s mitigation strategies to prevent such destruction from happening again. Video credit: Town of High River