The PEGG April 1992

The Unstoppable Alice Payne, P.Geo.

The Dean of Women was threatening to expel her.

It was 1961 and Alice Payne, a third-year geology undergrad at the University of Alberta, had signed up for the annual class field trip to the mountains. The one-week outing was a vital part of her structural geology course—a chance to learn hands-on skills she’d need for employment.

The problem? She was the only woman on the list.

Going on the field trip simply wouldn’t be proper.

Determined to take part, young Alice borrowed a tent and convinced some women who were her friends, to come along as chaperones.

She was not expelled, approval was granted, and she headed off to Cranbrook, B.C., to study rock outcrops and mapmaking.

It wasn’t the last time she would face barriers as a woman geologist. But nothing would stop her from doing what she loved.

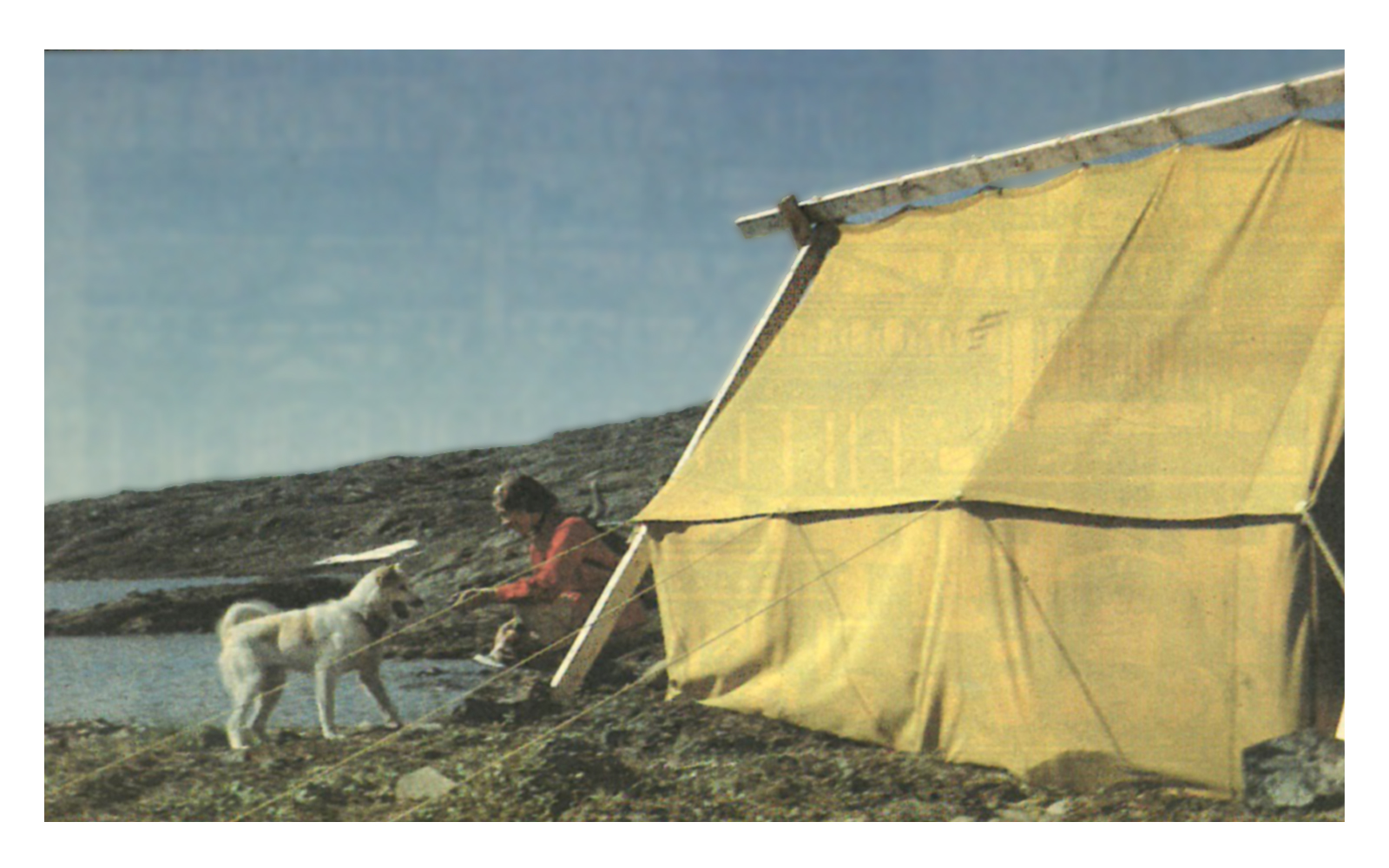

Alice – 1961 with chaperone: Alice Payne, P.Geol., (right) on the 1961 University of Alberta geology field trip to Cranbrook, with one of her friends/chaperones. The women slept in a tent while the men students stayed in cabins.

Photo courtesy of Alice Payne, P.Geol.

“One of the biggest challenges I faced in my career was the idea that women had no place in this business. But I never thought of quitting. I knew I could do it,” says Payne, reflecting on a 35-year career as a mining and petroleum geologist.

Her vocation took her from the backwoods to the boardrooms. Payne was the first woman president of the Canadian Society of Petroleum Geologists.

It all started in her childhood. Payne’s father owned a gold mine in Yellowknife and nurtured her curiosity for geology. He let her tag along on prospecting expeditions and gave her lessons in how to stake a claim. Payne was thrilled when her dad convinced superstitious miners to let her go underground so she could get a close-up look at gold veins.

“That’s where I got the bug,” she says. “I thought I’d be a prospector, too.”

Growing up in the Northwest Territories, Alice Payne, P.Geol., dreamed of being a gold prospector like her father, Tom. In this photo from the 1940s, Tom takes Alice (left) and her younger sister Elizabeth out for a paddle at Jolliffe Island in Yellowknife.

Photo courtesy of Alice Payne, P.Geol.

While attending school in Edmonton, she was advised by a guidance counsellor to seek a more suitable profession. Perhaps teaching or nursing?

Annoyed, Payne left his office more determined than ever to live her own story and not someone else’s.

After graduating with her geology degree in 1962, she sent out resumes signed only A.V. Payne. Employers wouldn’t screen her out for being a woman. Her strategy got her interviews, but no job offers.

“I was so naive. Nobody would hire a woman to work in the field,” Payne remembers.

She was excited to accept a job in Ottawa at the Geological Survey of Canada. But the survey would only let her analyze rocks in a lab. She’d heard that one before.

Payne soon decided to go back to university to complete a master’s degree in geological age dating. Her research took her into the wilds of Ontario, all the way up to the Arctic.

She thought the extra experience might help her land her dream job.

When it didn’t, she did what any enterprising geologist would do. She started her own company.

Great Slave Lake mapping: Alice Payne, P.Geol., with her professors, a cook and a field trip assistant, take a break while on a field trip to the east arm of Great Slave Lake in the mid 1960s.

Photo courtesy of Alice Payne, P.Geol.

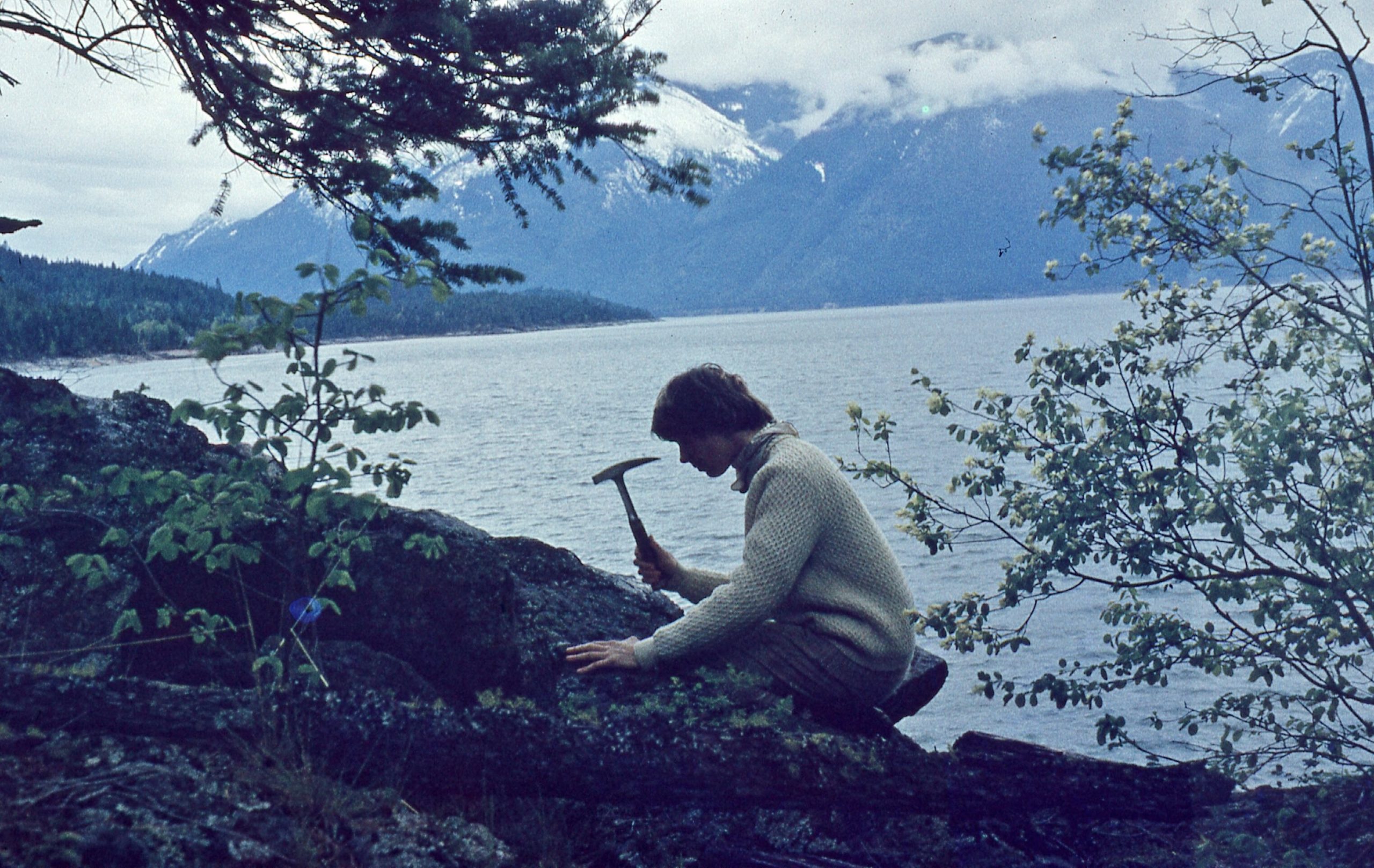

Hammering away with her rock hammer on a field trip to Jasper in the early 1960s.

Photo courtesy of Alice Payne, P.Geol.

Lone Lady – among 14 men at camp on Tree River, near Coppermine, while doing M.Sc. thesis work

The PEGG April 1992

Over the next 15 years, she got married, raised two children, and did small mining contracts, everything from gypsum and coal exploration to mapping bedrock for Syncrude’s new tailings pond dam.

“I did many interesting things and I had fun doing them,” she says.

Times and attitudes slowly changed.

In 1979, Payne decided to look for more stable work, accepting a job offer from Gulf Canada in Calgary. Not only could she do field trips, but they were in places like Florida and the Bahamas. Utilizing her mining background, Payne developed new ways to search for petroleum. Her talent was recognized with promotions into supervisory roles and then management.

A long-time volunteer with the Canadian Society of Petroleum Geologists, she was encouraged to run for president in 1992. To her surprise she won, becoming the first woman president in the society’s 65-year history.

After retiring from Gulf in 1995, Payne returned to consulting for several more years. Among her other achievements, she wrote a book about her father, served on APEGA Council, and helped found the Alberta Science and Technology Leadership (ASTech) Foundation.

She also helped found Operation Minerva, a mentoring program that helps young women explore STEM careers.

Payne’s advice to women geologists today? It reflects her own experience. And it’s timeless:

“Be versatile in your education. Diversify. Get a broad background. Seek mentors to help you along the way. And don’t give up. Never give up.”

The PEGG September 2000

Alice Payne, P.Geol., with her geological hammer and various rock, fossil and oil samples collected through her career. She is holding gold ore from the Con-Rycon Mine in Yellowknife, where her father staked claims. Active in several professional organizations throughout her career, Payne served on APEGA Council and volunteered on the Board of Examiners for years. She also received an honorary doctorate from the University of Calgary and was named to the Order of Canada. Retired now, she lives on a ranch west of Calgary.

Photo courtesy of Alice Payne, P.Geol.