Photo courtesy of the Currie family

Surviving Antarctica: Geoscience Adventure Ends in Tragedy

Explorer. Adventurer.

Survivor.

When Don Currie, P.Geol., graduated from the University of Alberta’s geology program in 1958, he never expected to include these words on his résumé. But in 11 short years, he would earn every single one.

Currie started his career as a prospector in Yukon before moving to Saskatchewan to drill for oil. There, he met the love of his life and future wife, Olga (Ollie) Warnyca.

His travels eventually led him to accept a geology position studying groundwater with the Research Council of Alberta (RCA).

Exploring the world’s coldest desert

“Currie, do you want to go to Antarctica?” asked Dr. Tom Berg. Currie and Berg met while working at the RCA, where their love of geology and adventure quickly cemented their friendship. It took Currie only a nanosecond to respond. A year later, the two took a leave without pay from the RCA and were on their way to the southernmost continent.

As part of his PhD research at the University of Wisconsin, Berg received the opportunity to explore the McMurdo Dry Valleys in search of uranium and thorium. Currie was the perfect candidate to analyze core samples and study the heat flow and seismic velocities at drilling sites during the expedition.

The two men landed at Williams Field in a Lockheed Super Constellation. “I remember we both knelt down and kissed the ice runway,” wrote Currie in his memoir about the once-in-a lifetime adventure that would leave two men dead. It was October 1969.

They continued north to McMurdo Station, a United States research station on the north tip of Ross Island and Antarctica’s largest community. Built on volcanic rock and enduring temperatures as cold as -50°C, the station supported 200 scientists, military personnel, and civilians year-round.

“To be treated by the National Science Foundation and the U.S. Navy to the Antarctic experience, exclusive of the sadness, was an honour and a privilege,” Curry wrote.

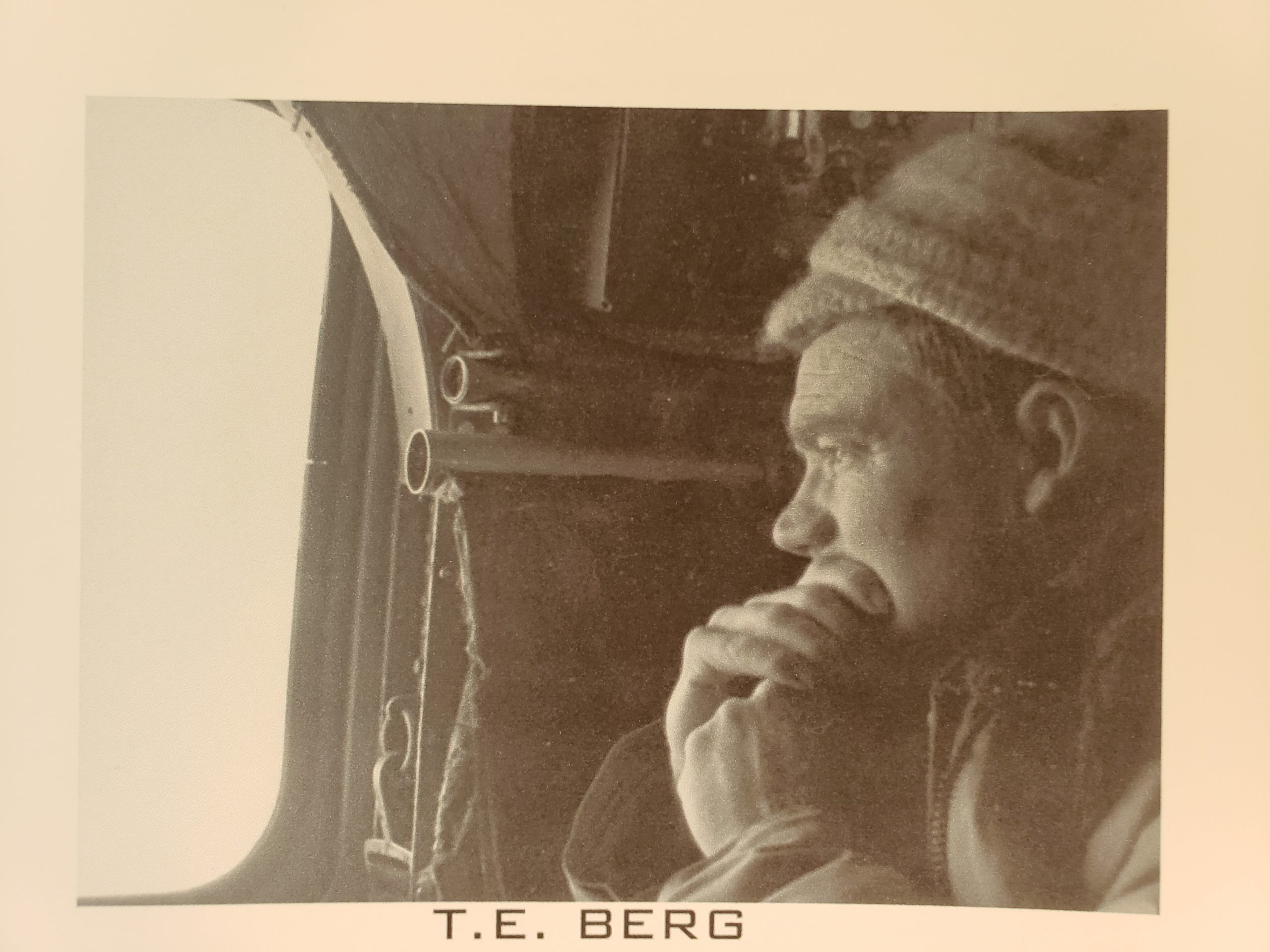

Don Currie, Dr. Tom Berg, and Commander James Brandeau loading the Sikorsky that would later catch fire and crash in Antarctica. When asked if he would ever fly in a helicopter again, Currie was always quick to reply that he didn’t have any trouble getting into the one that rescued them.

Photo courtesy of the Currie family

“It was like someone hitting the side of a building with a 2×4”

On the morning of November 19, 1969, Currie and Berg boarded a Sikorsky helicopter, joined by two New Zealand filmmakers, Jeremy Sykes and Samuel Grau; two crew members, Gordon Little and Claude English; and the pilot and co-pilot, Commander James Brandeau and Lieutenant Michael Mabry.

As they headed towards Wright Valley, fuel from a suddenly ruptured line ignited, causing the magnesium floor to burst into flames—the helicopter slammed into the mountainside. The impact threw them like rag dolls, and the rescue sled broke loose and crashed on the heads of Berg and Sykes—killing them instantly.

Because of the dangerous inflammability of magnesium, the helicopter was consumed by fire, with only a piece of the tail rotor remaining. “Everything else gone, like I mean gone. Black ashes. No flares, no mirrors, no radio,” wrote Currie.

Mabry and Little trudged 13 kilometres to an emergency radio station for help. The rest of the injured crew waited eight hours in below-zero temperatures with only the rotor as shelter. Currie’s parka and wind pants had burned in the crash—while he was wearing them.

Their eventual rescue was bittersweet. “That’s when the sadness hit. All the movies say it should be joy, but it wasn’t. We helped the New Zealander into the chopper, and then the crew man, pilot and I embraced with tears in our eyes. We mounted the machine and left the scene.”

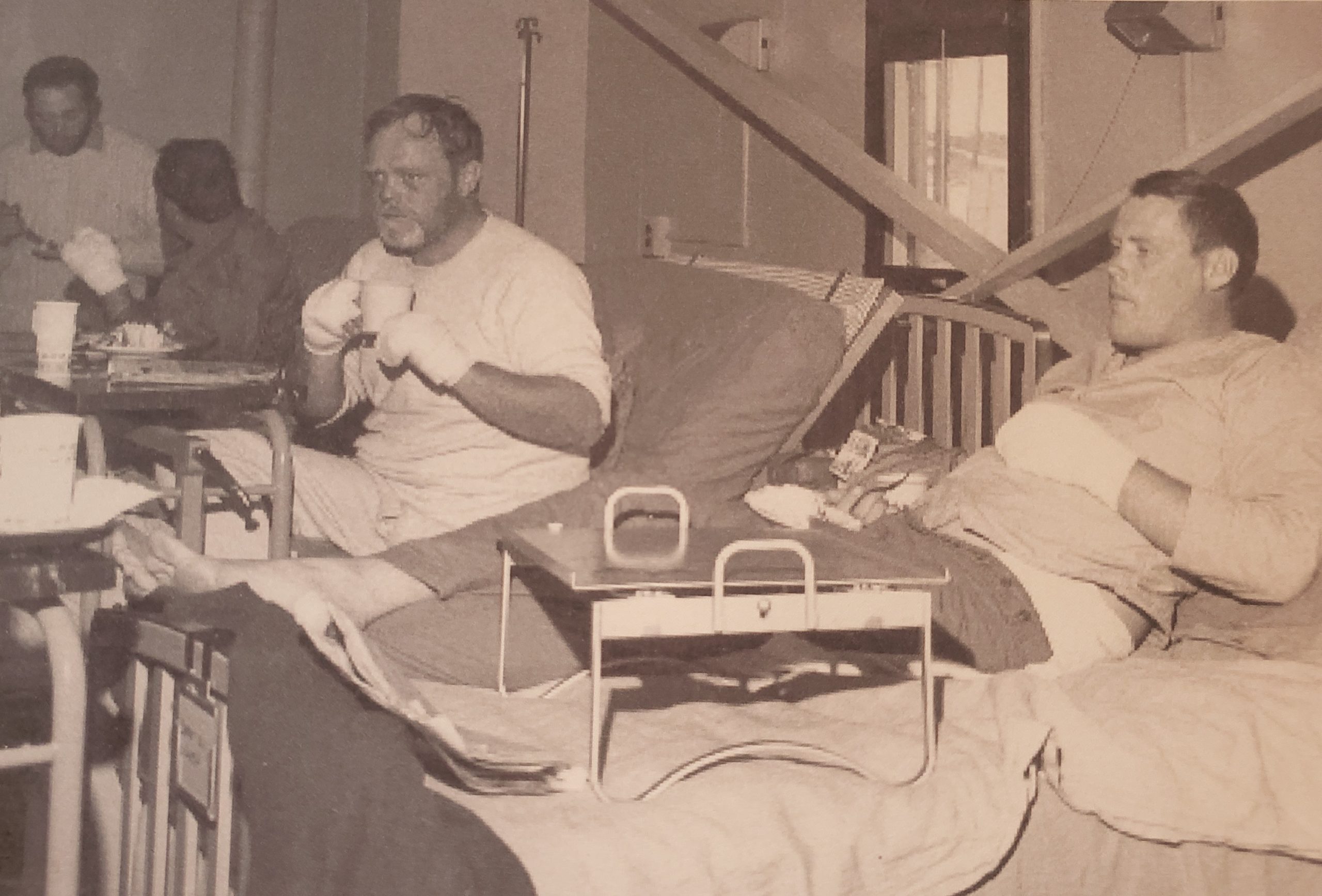

Currie (right) and Brandeau (left) being treated for second-degree burns.

Photo courtesy of the Currie family

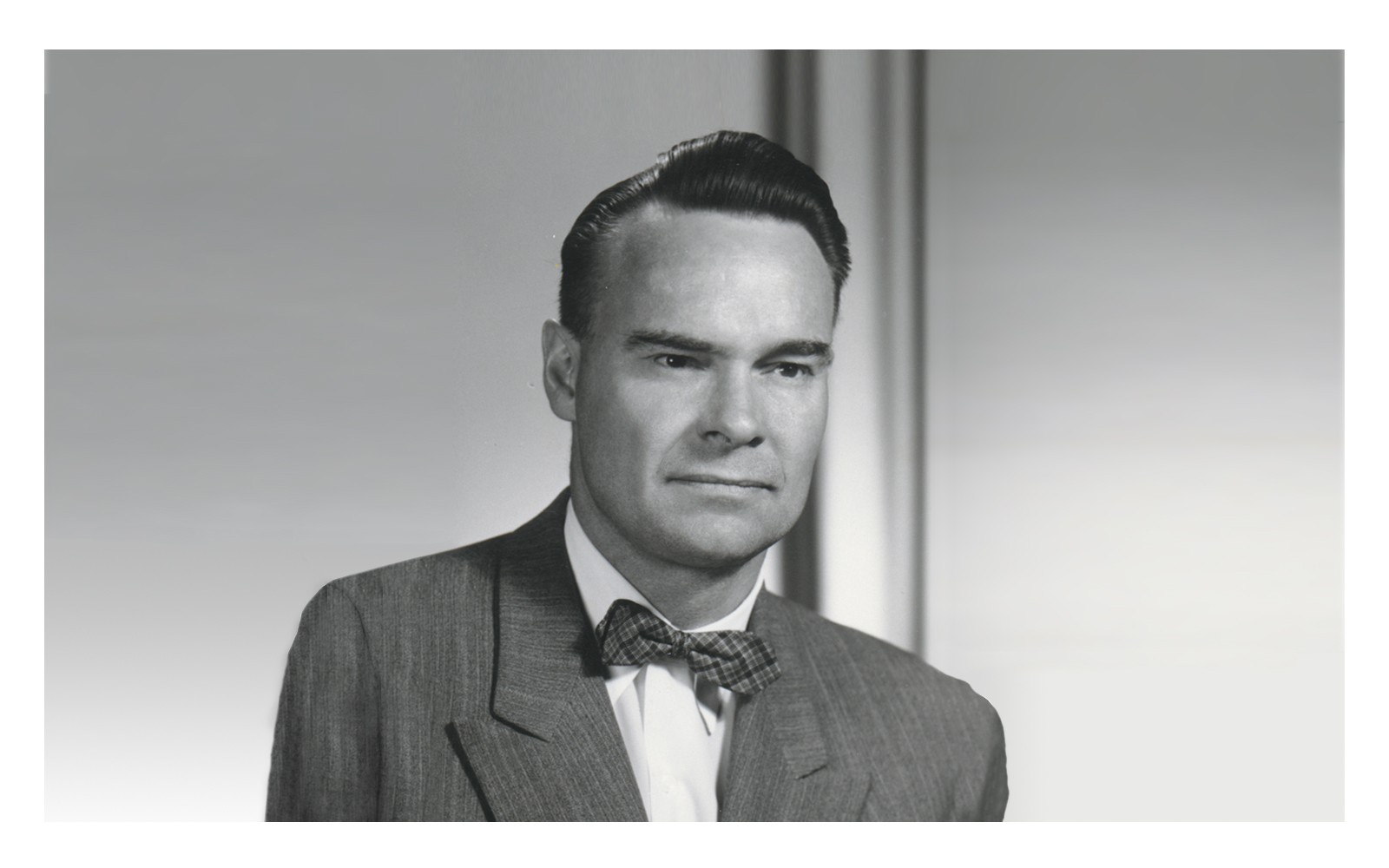

Dr. Thomas Berg, associate research officer with the Research Council of Alberta (1969). Dr. Berg and Jeremy Sykes, a film director from New Zealand, did not survive the helicopter crash.

Photo courtesy of the Currie family

Home is where the heart is

Currie continued working as a geoscientist with the RCA, but this time he limited his adventures to the safety of the boardroom. Knowing the importance of giving back to one’s profession, he helped guide the future of APEGA as a Councillor (1979 to 1981), and he shared his passion for education by serving on the University of Alberta Student Liaison Committee for almost a decade (1979 to 1988).

Even after retirement, Currie was a key player in industry. In 1986, he became the managing director of the Alberta Chamber of Resources and served in the position for 15 years, lobbying the government to invest in Alberta’s oil sands. At the same time, he was the managing director for the Construction Owners Association of Alberta (COAA). To this day, the COAA bestows the Don Currie Award of Recognition upon one member each year who demonstrates long-standing and dedicated service.

Of course, Currie’s true love was always his wife, Ollie. After 56 years of marriage, Don and Ollie Currie passed away within eight months of each other in 2018.

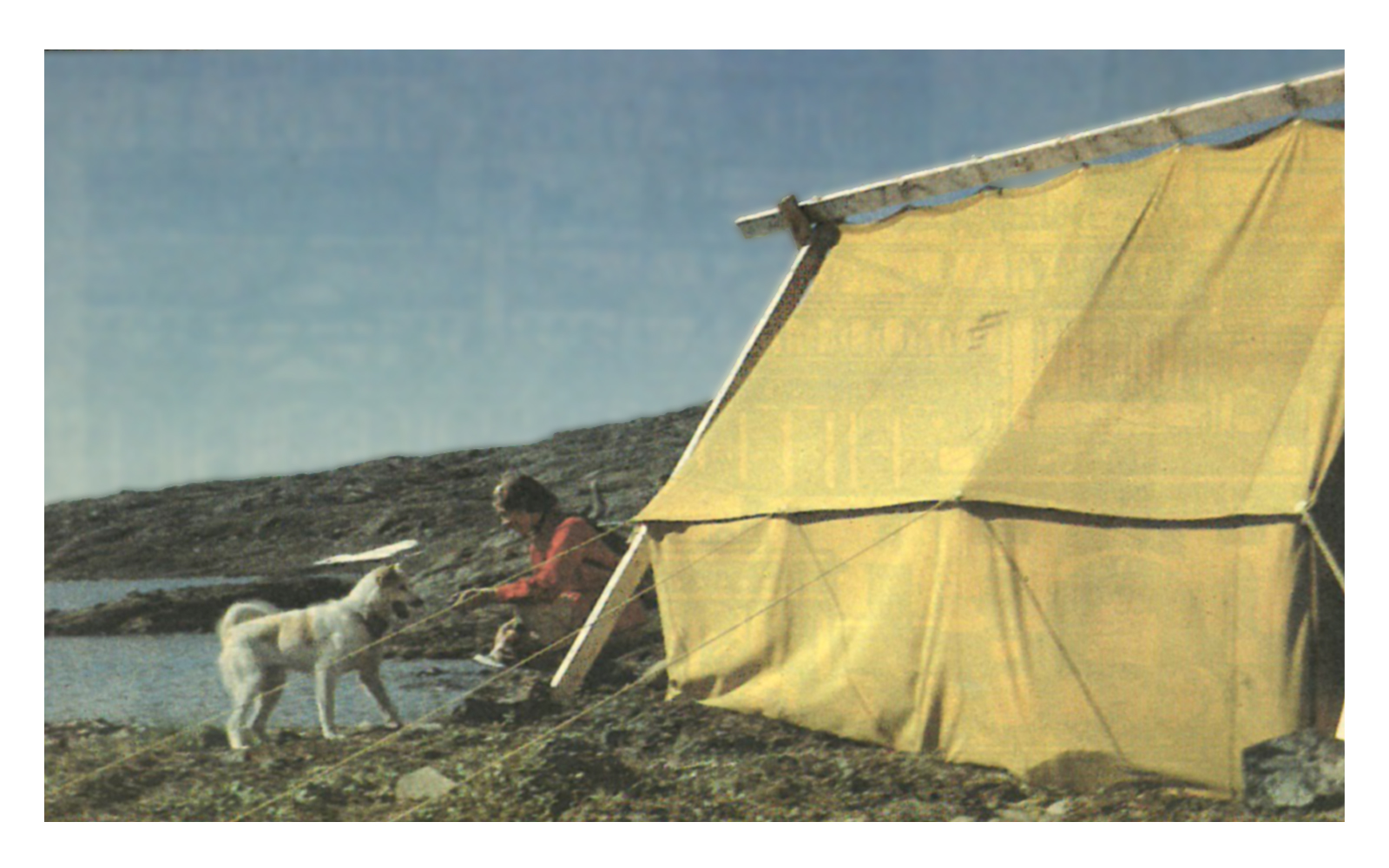

Don and Ollie Currie. Don’s professional awards include the United States Antarctic Service Medal (1977); an APEGA Honorary Life Membership (1986); the APEGA LC Charlesworth Professional Service Award (1998); an Honorary Engineers Canada Fellowship (2009); and a Geoscientists Canada Fellowship (2014).

Photo courtesy of the Currie family