Photo courtesy of Laurence Andriashek, P.Geol., Alberta Geological Survey

Paskapoo Rock Revival: Preserving the Alberta Legislature

A restoration project underway at the Alberta Legislature will give the 107-year-old heritage building a new lease on life.

After an engineering study found 18,000 defects on the building’s porous sandstone exterior, a team of masonry experts is now painstakingly removing and replacing each crumbling and broken stone. Repair work began in the summer of 2019 and is expected to wrap up in the fall of 2021, helping preserve the building for the next 100 years.

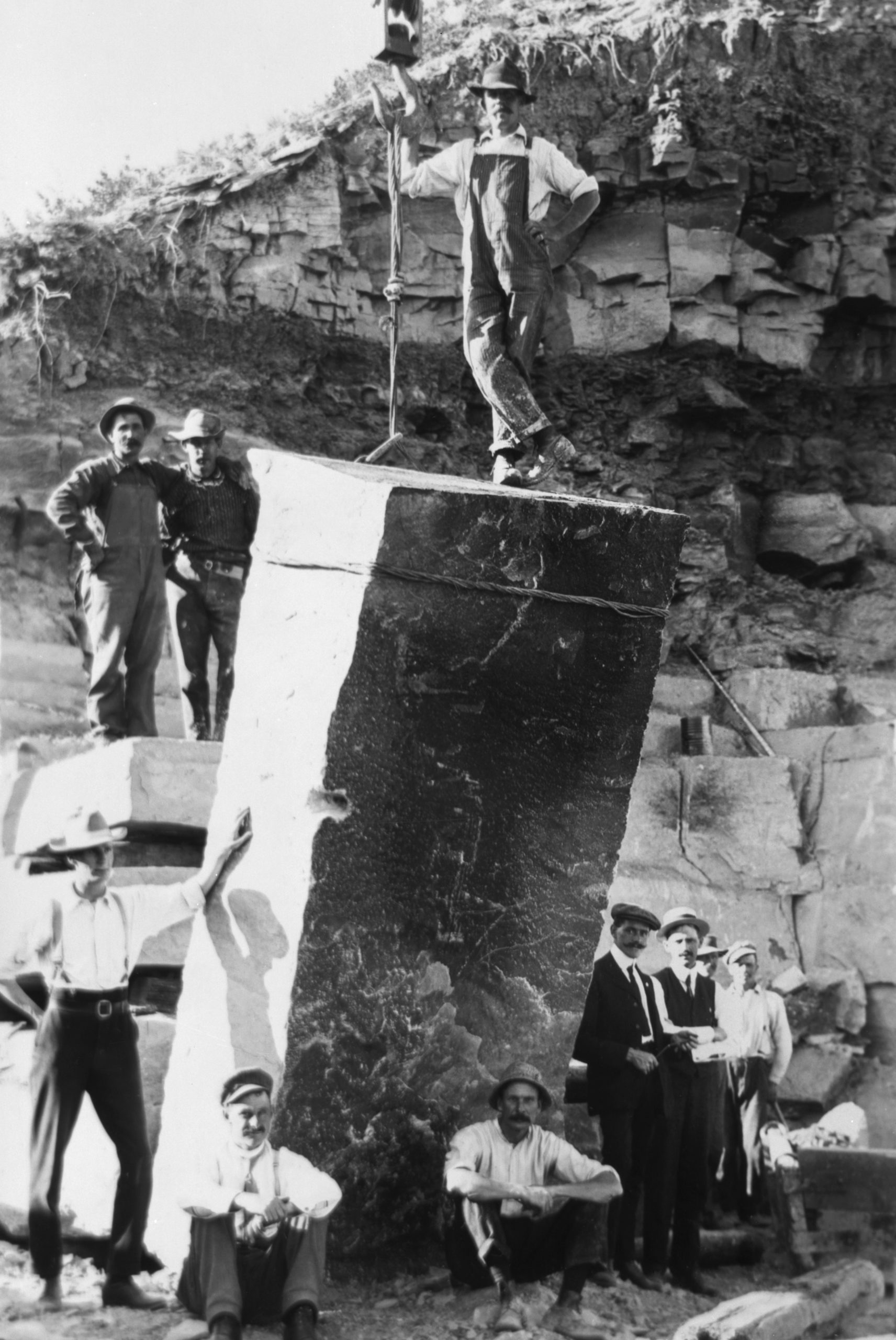

Most of the sandstone used to build the legislature’s upper stories was mined at the Glenbow Quarry, which operated from 1907 to 1912. Located a few kilometres from Cochrane in what is now Glenbow Ranch Provincial Park, the quarry harvested chunks of 58- to 65-million-year-old sandstone from the Paleocene Paskapoo Formation.

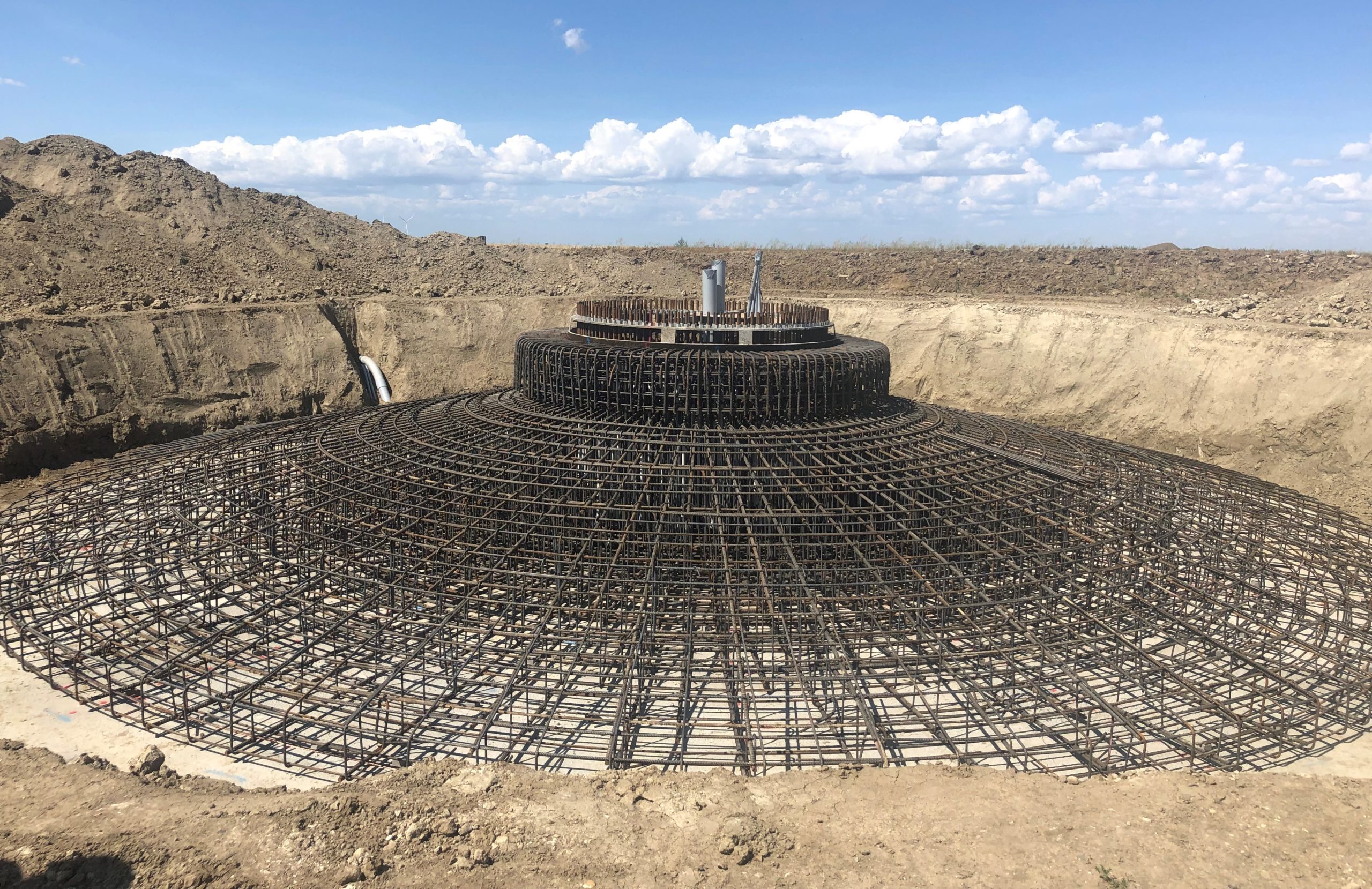

Stonecutters with a block of Paskapoo sandstone in a quarry near Calgary, circa 1912.

Photo courtesy of Glenbow Archives, Archives and Special Collections, University of Calgary NA3267-53

In rock years, that’s considered young.

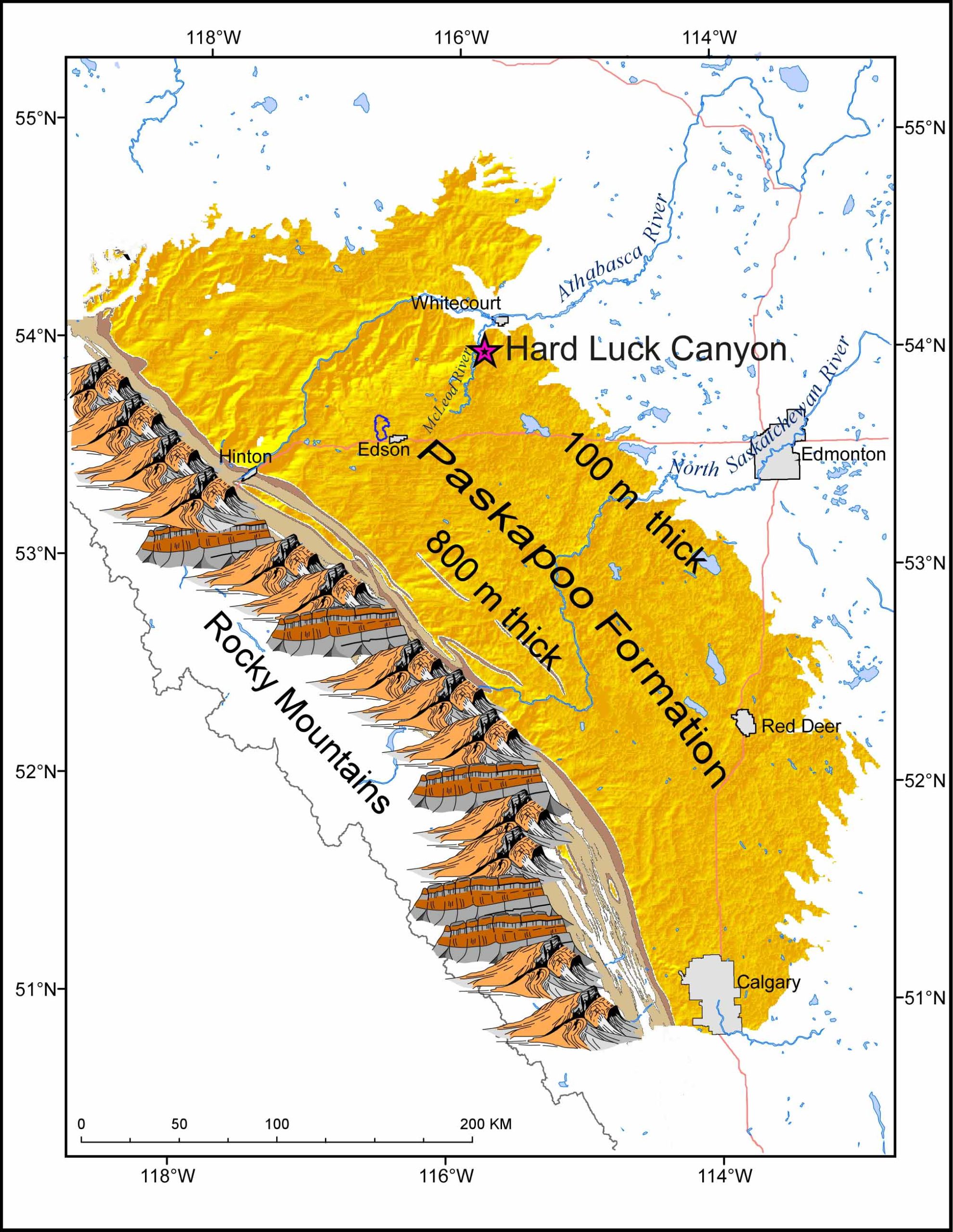

In fact, the Paskapoo Formation—found east of the Rockies, from Fox Creek north to south of Calgary—is one of the youngest bedrock formations in the province.

“Because the rocks are so young, the pores between the sand grains haven’t been fully filled in with cement, so the Paskapoo sandstone is quite porous,” notes professional geologist Laurence Andriashek.

Water can easily travel through the pores, he explains, making the Paskapoo Formation one of the largest sources of fresh groundwater in Western Canada.

Alberta’s Paskapoo Formation is found east of the Rockies from Fox Creek north to south of Calgary.

Image courtesy of Alberta Geological Survey

The relative youth of this sandstone is also what made it a popular building material in Alberta in the early 20th century. Not only was it easily accessible—and therefore affordable—but it was easy to cut and carve.

“It’s not super hard for cutting, but it’s hard enough to hold its shape,” says Andriashek. Its permeability, however, also made it susceptible to damage from freeze and thaw cycles, which ultimately led to its downfall as a building stone.

“Eventually, it was abandoned in favour of Tyndall limestone from Manitoba, which is much more durable,” he says.

Cemented Paskapoo sandstone was used to build the Alberta Legislature’s upper stories. Close examination of the stones reveals sedimentary structures dating back 58- to 65-million years.

Photo courtesy Laurence Andriashek, P.Geol., Alberta Geological Survey

As part of Andriashek’s work with the Alberta Geological Survey, a branch within the Alberta Energy Regulator, he has studied and mapped the Paskapoo’s groundwater aquifers. He also has a special fondness for portions of the Paskapoo that can be viewed above ground.

“My interest is not solely in groundwater. There’s a more visceral association with the Paskapoo,” he says.

“Although much of the Paskapoo Formation is made of muddy sediments, Paskapoo sandstone tends to be very prominent in river exposures, even more so when you’re canoeing rivers like the North Saskatchewan. When you canoe from Rocky Mountain House to Drayton Valley, for example, or from Hinton to Whitecourt, you go through some of the most spectacular Paskapoo exposures and vertical walls. In Alberta, having canyons like that is a bit of a rarity.”

It’s more typical to find bentonite clay layers along Alberta riverbanks, which tend to swell and slump from water erosion. “You don’t get the cliff-forming walls that the Paskapoo sandstone produces,” says Andriashek.

Sandstone outcrops from the Paskapoo Formation along the headwaters of the North Saskatchewan River.

Photo courtesy Laurence Andriashek, P.Geol., Alberta Geological Survey

But canoeing isn’t necessary to view Paskapoo formations up close.

In Woodlands County near Whitecourt, fascinating 25-metre vertical cliffs are exposed at Hard Luck Canyon, which is easily accessible along groomed hiking trails, says Andriashek. And a drive along the Cowboy Trail—Highway 22 from Drayton Valley south to Calgary—also travels through Paskapoo formations.

It’s another favourite for Andriashek.

“It’s just some of the most beautiful landscape in Alberta. It’s got high-relief rolling hills. I could go on and on,” he laughs.

Laurence Andriashek, P.Geol., and Kara Kennedy, manager of Parks and Recreation for Woodlands County, at the unveiling of geological interpretive signs in Hard Luck Canyon, which is part of the Paskapoo Formation. Andriashek, with the Alberta Geological Survey, designed the signs for Woodlands County.

Photo courtesy of Laurence Andriashek, P.Geol., Alberta Geological Survey

Built to last

Paskapoo sandstone was not the only stone used to build the Alberta Legislature.

Marble from Quebec was used to panel the walls of the rotunda and form the grand staircase, while the chamber is adorned with green serpentine marble from Pennsylvania. Granite from Vancouver Island was used in the building’s basement and first floor. Larger slabs of sandstone, imported from Ohio, were also used to build the Corinthian pillars in the legislature’s main portico.

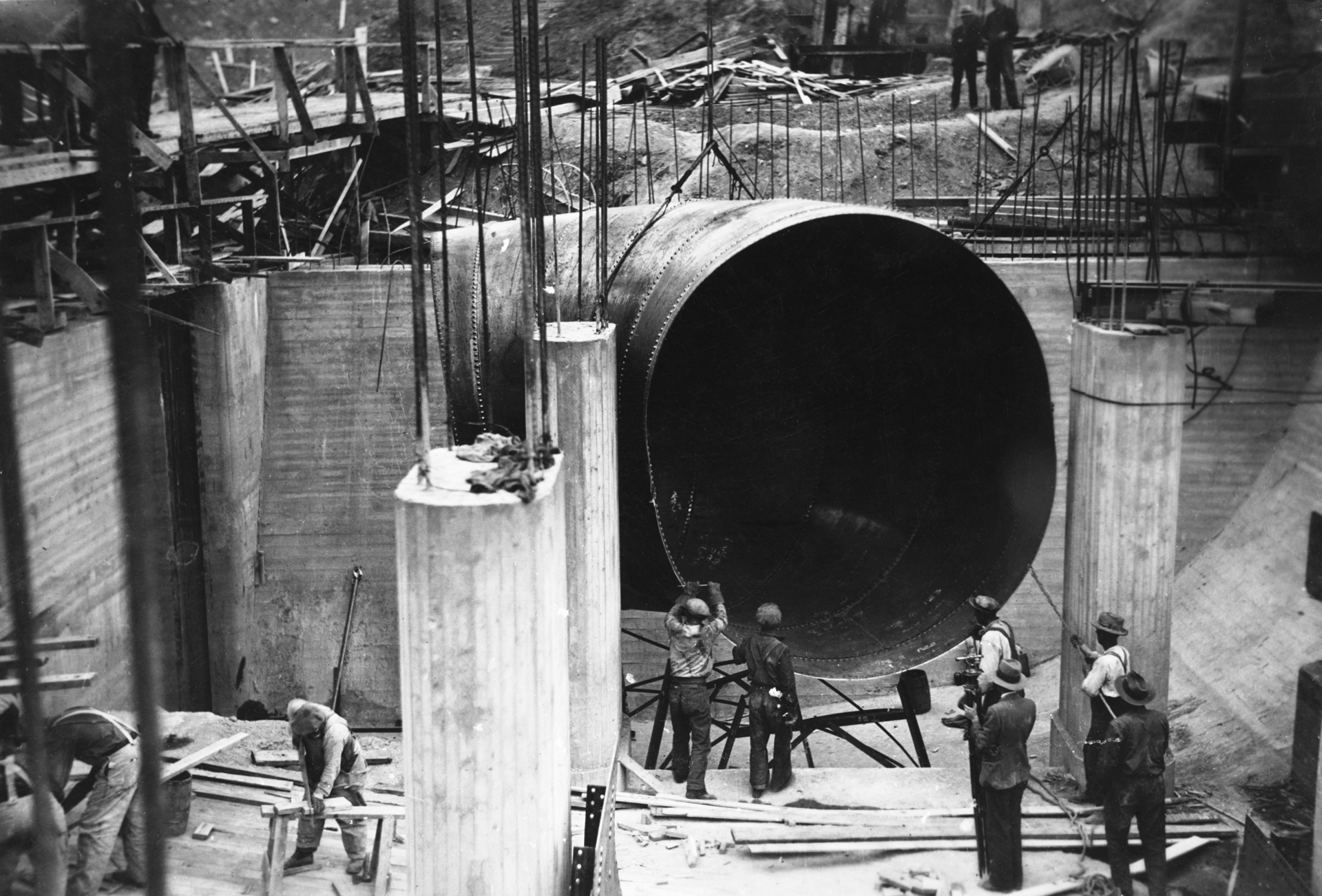

The building site for the legislature, on the north bank of the North Saskatchewan River, was excavated in 1907 to a depth of about four metres. The ground was mostly hard glacial clay with a few boulders.

In addition to stone, the legislature’s foundation walls were built from concrete. There are 91 interior column foundations, including those supporting the dome, while the building’s frame, up to the main floor level, is made from 1,100 tonnes of steel.

View of the material yard during the construction of the Legislative building, 1909.

Courtesy of Provincial Archives of Alberta A11027

Engineered for the future

The current restoration isn’t the first time professional engineers have been involved with efforts to protect the historic structure. Engineering consultants led work on the building’s terracotta dome replacement in 2012, as well as a previous sandstone restoration project completed in 1994.