Photo courtesy of Laughing Dog Photography

How Alberta Engineering Helps Battle Diabetes

The article in Time magazine caught his eye. “Biomedical engineering,” it blared. “The career of the future.”

The young X-ray technician didn’t know it then, but the story would change his life—and, eventually, the lives of thousands of Type 1 diabetes patients around the world.

Ray Rajotte, P.Eng., PhD, recalls thinking that biomedical engineering might be a great way to combine his interests in technology and medical research. A good thought, that one.

“I could have become a medical doctor, but I thought biomedical engineering would be an exciting area to be involved with,” says Dr. Rajotte. “And it certainly has been.”

Back in the mid-1960s, Rajotte was working at Edmonton General Hospital. Biomedical engineering was an emerging field focused on improving health care through engineering.

The University of Alberta’s biomedical engineering department was still just a vision, so Rajotte enrolled in electrical engineering. But he took all his third- and fourth-year electives in medicine—everything from anatomy to physiology to biochemistry.

He completed his bachelor’s degree in 1971, followed by a master’s in 1973. In 1975, he became the U of A’s first PhD graduate with a biomedical engineering designation on his diploma.

Rajotte’s graduate research focused on using engineering to develop new techniques for isolating, cryopreserving, and thawing pancreatic islets. It became his life’s work.

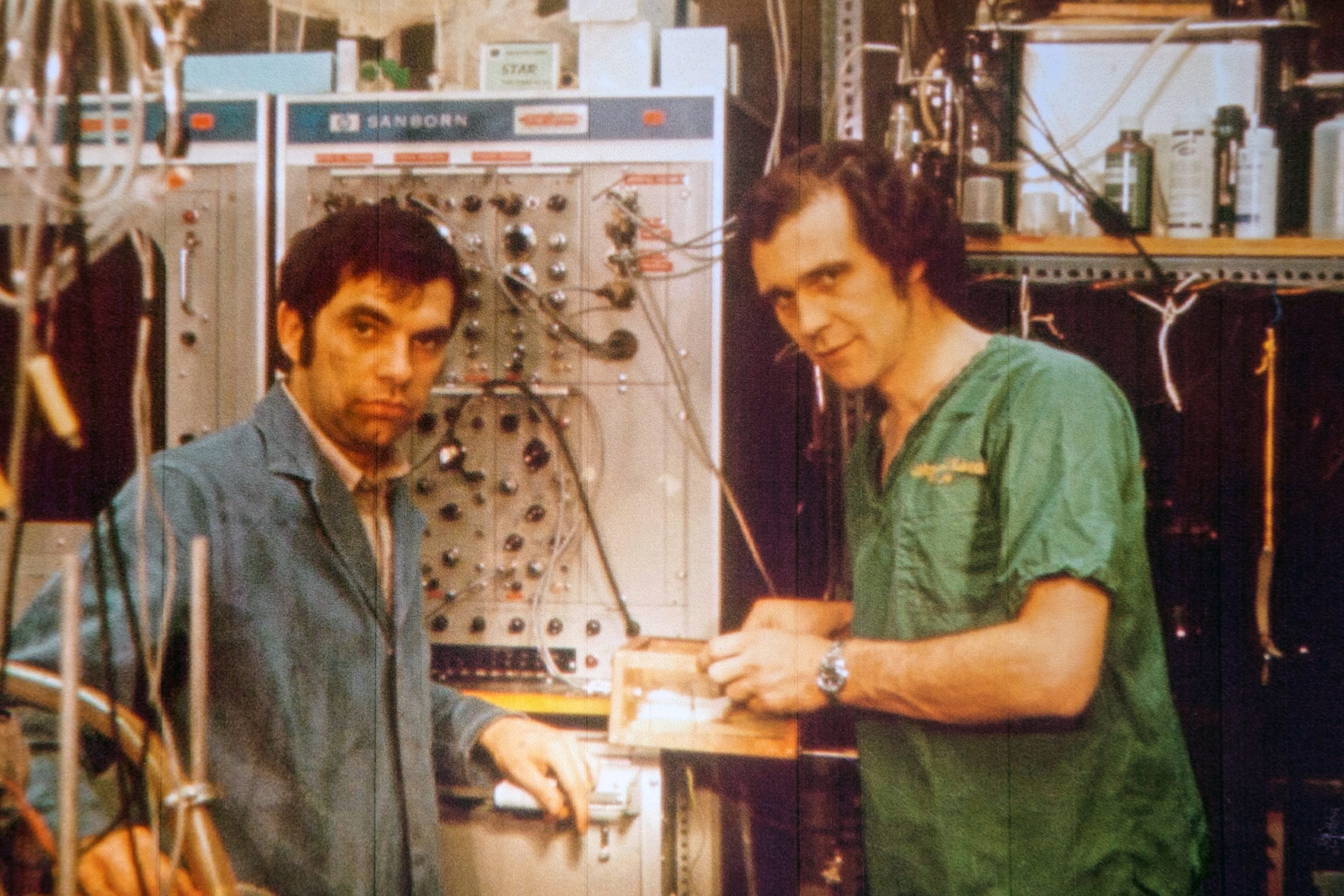

Ray Rajotte 1973: Ray Rajotte and Geoff Voss freeze islets at the University of Alberta in 1973. Voss, an electrical engineering professor at the U of A, and physician Dr. John Dosseter supervised Rajotte’s graduate research and were his early mentors.

Photo courtesy of Ray Rajotte, P.Eng.

Islets are insulin–producing cells that control blood glucose levels. They don’t work properly in people with Type 1 diabetes, who must take regular insulin injections to survive. Rajotte and other pioneering researchers believed that islet transplantations might one day lead to a cure.

This possibility motivated Rajotte to continue his islet cell research at the U of A, long after completing his PhD. His persistence paid off in the late 1970s when he was able to successfully isolate and cryopreserve islets in diabetic rodents, curing them of the disease.

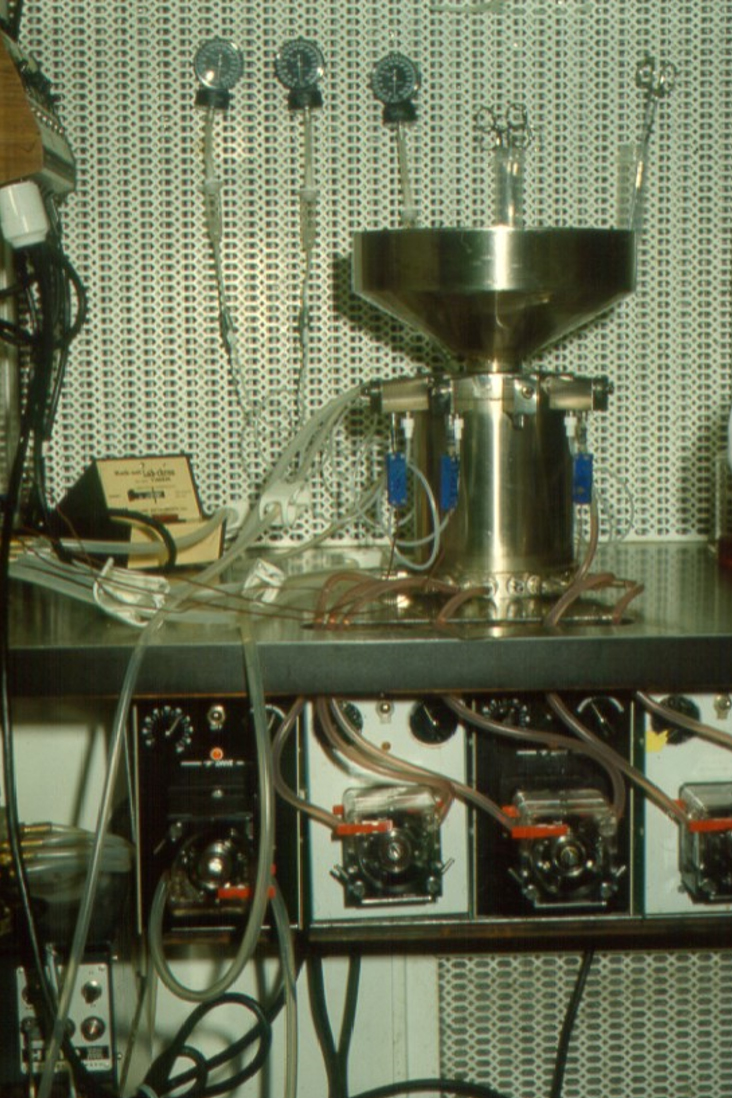

“It took a lot of modifications and my engineering skills to develop tools to isolate the islets. I even had my own machine shop, so when I wanted something specialized for islet isolation, I’d just go and build it. Perfusion pumps, isolation chambers. Stuff you can’t just buy off the shelf.”

A perfusion machine, engineered by Ray Rajotte, is used to help isolate islets from a human pancreas.

Photo courtesy of Ray Rajotte, P.Eng.

The next step was clinical trials with diabetic patients. “The challenge was to make the islet procedure work in humans,” Rajotte says.

Before that could happen, he needed to build a transplant team.

“I always thought of islet transplantation as a big puzzle—bringing in people to help solve the puzzle, surrounding yourself with smart people.”

By 1982, his surgical team was in place. Including doctors Garth Warnock, Norm Kneteman, and Eddie Ryan, the team made medical history in 1989, successfully completing Canada’s first islet cell transplants using technology developed by Rajotte during his PhD work.

Their first two patients were able to reduce their insulin intake but ultimately lost islet function. For the next three transplants, the team doubled the number of islets and added freshly isolated islets to the mix. Before, they had used cryopreserved islets only.

The results were encouraging: one of the three patients was able to stop taking life-saving insulin injections for three years, and another for two years.

“We published our results and we were inundated with requests,” says Rajotte. “Whatever we learned, we shared with the world.”

Despite their achievement, much work remained. Worldwide, only about 10 per cent of transplant recipients were able to stop using insulin.

Progress stalled for a time, but it moved forward again when Rajotte made another key addition to the islet team. Dr. James Shapiro, a transplant surgeon and expert in immunology, came on board. So did scientists Greg Korbutt and Jonathan Lakey. Several adjustments were made to the islet transplant procedure, including the use of less-toxic anti-rejection drugs.

New trials began in 1999. This time, seven Type 1 diabetes patients received transplants. A year later, all seven remained insulin independent.

The Edmonton Protocol, as it’s now known, was hailed as the biggest breakthrough in diabetes treatment since the discovery of insulin. Today, it remains the gold standard, with about 60 per cent of transplant patients remaining insulin independent for at least five years after transplantation.

Rajotte built the framework for the Edmonton Protocol’s success—a vision almost three decades in the making. But he’s modest about his contributions, and quick to credit the many mentors and colleagues who inspired and motivated him along the way.

“You have to be a little visionary, look at the problem, and say, how do I solve the problem and how do I bring in people to help solve it? I’ve been very fortunate to work with some outstanding collaborators and graduate students.

“Our research has been very much a team effort, over the years, to bring us where we are today.”

Alberta Order of Excellence Award recipient Ray Rajotte, P.Eng., PhD