APEGA Photo

Building the Future: APEGA Science Olympics

They’ve built aqueducts from aluminum foil and self-propelled cars using mousetraps, CDs, and balloons. They’ve dug for fossils in sedimentary rocks and designed water-powered electricity generators with cardboard, recycled materials, and duct tape—lots of duct tape.

There have been egg launchers and elastic-powered cars. Rube Goldberg machines, water filtration systems, and miniature Mars rovers. And, of course, pasta and popsicle-stick bridges.

These are just some of the hands-on engineering and geoscience problem-solving challenges K-12 students have tackled at the APEGA Science Olympics since the event was launched in 1993.

Working in teams, thousands of students from hundreds of schools across Alberta have had their communication, cooperation, and critical thinking skills put to the test.

“APEGA Science Olympics is a fun way to show students first-hand how engineering and geoscience impacts their lives,” explains Karl Jory, P.Eng., volunteer organizer for APEGA Science Olympics – Lloydminster.

The goal: to ignite students’ interest in science and math—and perhaps inspire a new generation of professional engineers and geoscientists.

Edmonton was home to the first APEGA Science Olympics, but the event has expanded over the years and now includes Calgary, Cold Lake, Fort McMurray, Lloydminster, Medicine Hat, and Red Deer.

Participants in the Calgary 2019 Science Olympics transporting their challenge.

APEGA Photo

From the very start, volunteers like Jory—professional engineers, professional geoscientists, engineers-in-training, geoscientists-in-training, university students, teachers, and parents—have played a vital role in the planning and execution of the APEGA Science Olympics. Supported by APEGA staff, volunteers develop the activities students participate in, serve as judges at the events, and act as role models and student mentors.

Jory, who has organized the event in Vermilion for the past four years, is continually amazed by the students’ ingenuity and enthusiasm. Teams from across the region participate, including Lloydminster and surrounding communities like Kitscoty and Marwayne.

“There’s always excitement in the air, a sense of curiosity. My favourite part is at the end of the day, seeing what students came up with. How they solved the problem we put in front of them,” he says. “You get a wide variety of solutions to the same problem. Sometimes you look at what students are doing, and you never would have thought to do it that way.”

Volunteers at the APEGA Science Olympics – Vermilion River in 2019, including Karl Jory, P.Eng. (front row, left).

Photo courtesy of Karl Jory, P.Eng.

Growing up in Mannville, about 80 kilometres west of Lloydminster, Jory’s love of math and science was nurtured by his junior high and high school science teacher, Mr. Bates.

“He would push me and try to get the best out of me, and was always willing to talk when I had questions,” he remembers.

A geotechnical engineer, Jory is paying it forward, mentoring students at APEGA Science Olympics and as an APEGA outreach volunteer, visiting local schools to talk about engineering and geoscience careers and their real-world applications.

Like erosion-control troughs, for example.

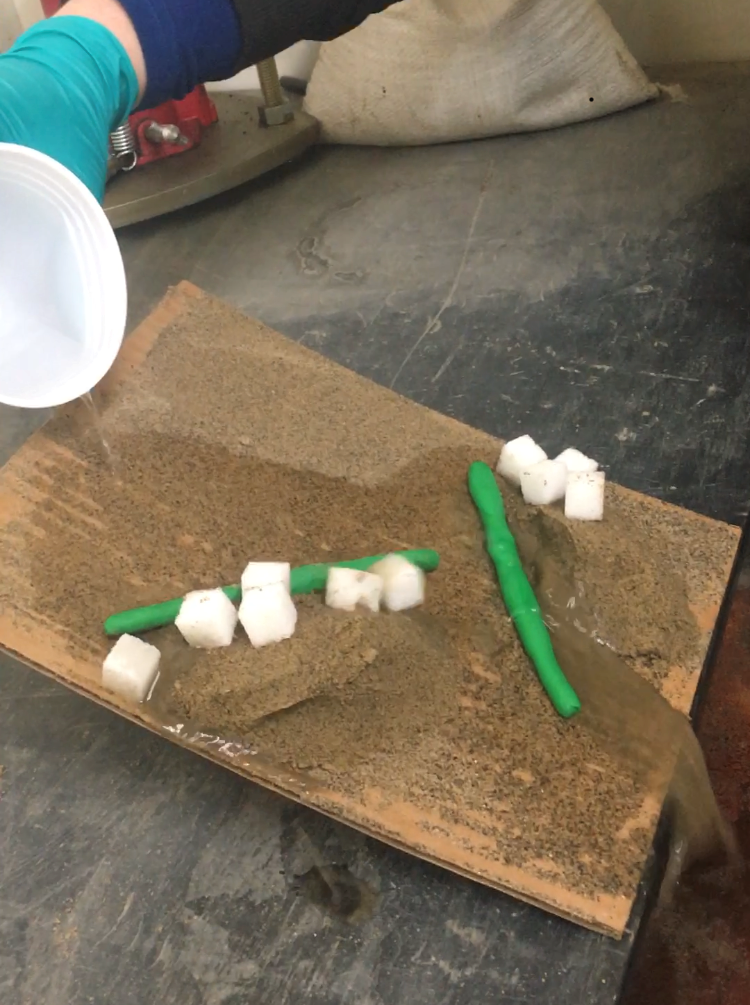

That’s what teams taking part in last year’s APEGA Science Olympics – Vermilion River were challenged to build as part of the Run-Off Rumble.

Students were armed with sand, cardboard, modelling clay, toothpicks, and screen mesh, and tasked with designing an erosion-control trough that would protect 10 sugar cubes from dissolving in a flood. Points were awarded for the least amount of erosion and the most bricks remaining intact after the flood.

The goal: to show students how professional engineers and geoscientists use erosion control, like culverts and spillways, to protect soil, hills, and slopes from eroding during heavy rain.

“It’s an afternoon to engage them, to get them thinking about engineering and geoscience, and all their possibilities,” says Jory.

The aftermath of the Run-Off Rumble erosion control challenge.

Photo courtesy of Karl Jory, P.Eng.