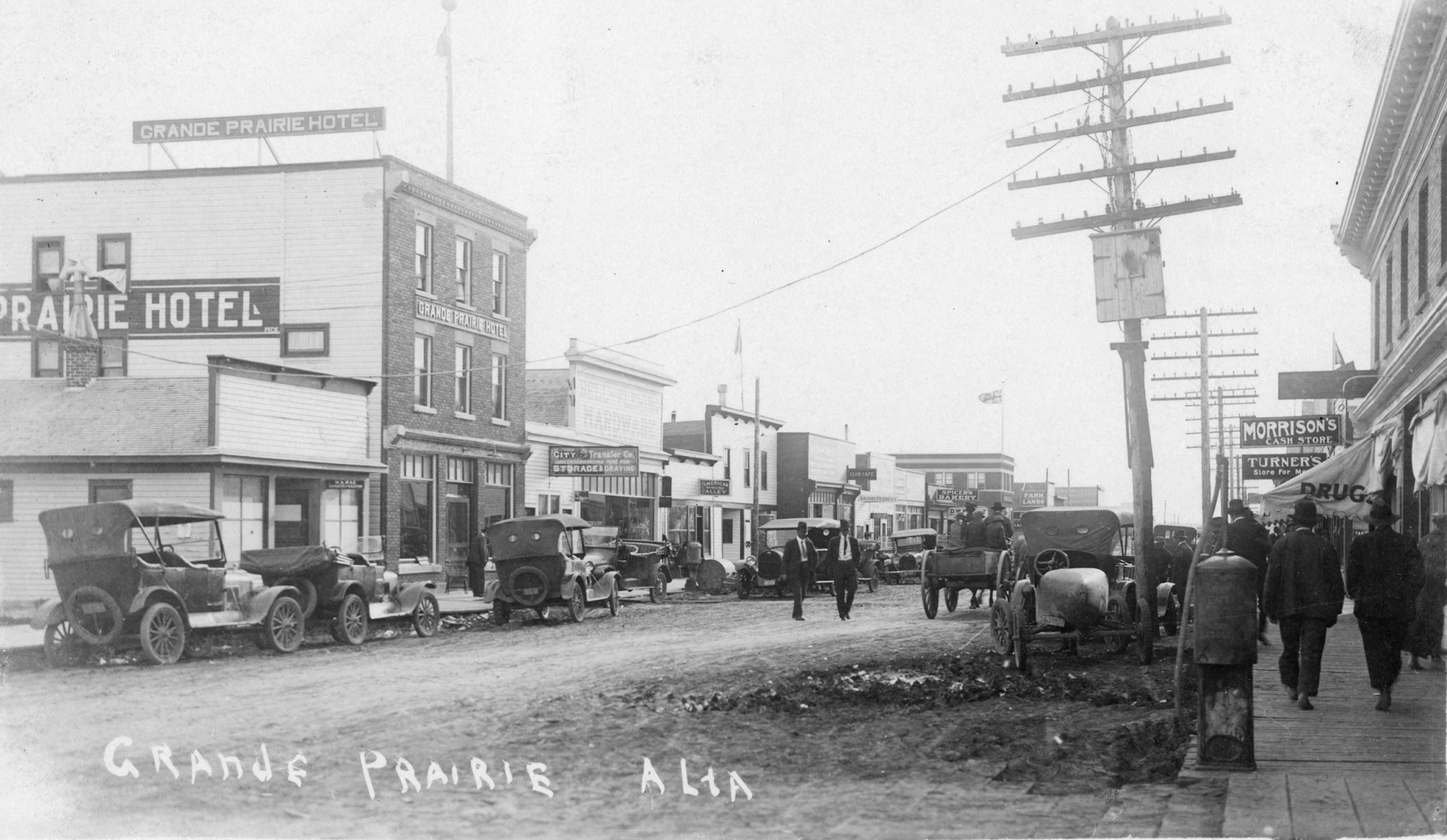

Glenbow Archives IP-14a-1828

Breaking New Ground: Alberta’s First Women Geoscientists

Alberta’s first women geoscientists were true trailblazers—sometimes literally. Whether climbing mountains to collect rock samples or examining microfossils in a lab, their work led to new discoveries and gave future generations of Earth scientists a better understanding of the world beneath our feet.

It wasn’t easy, though. They constantly had to prove their strength, stamina, and smarts. And prove it they did.

Dr. Grace Anne Stewart—Canada’s First Geoscientist

Leading the way was Grace Anne Stewart, PhD. A farm girl from Manitoba, Dr. Stewart was the first Canadian woman to earn a geology degree. It happened in 1918, in APEGA’s home province at the University of Alberta.

Stewart was also the first Canadian woman to receive a PhD in geology, this time from the University of Chicago in 1922.

As a PhD student, she spent two summers working at the Geological Survey of Canada in Ottawa. Men supervisors and colleagues, back then, were not always thrilled to have a woman in their ranks, so she had to endure some hostility.

Stewart persevered.

In 1923, she accepted a teaching position at Ohio State University and ended up spending 32 years there. Stewart became a geology professor, a respected researcher, and, after retirement from the university, an oilfield consultant in Calgary.

After her death, a friend of Grace Anne Stewart’s wrote that she was “a member of that band of pioneer women who refused to be deterred from qualifying as geologists because it seemed to be a masculine preserve.”

Stewart’s time in the oilfield was brief. For other pioneering women geoscientists, it was a much bigger part of their career.

Photo courtesy of Wikipedia

Dr. Diana Loranger, P.Geol.—Curiosity of Note

Nicknamed Madame Curious by her father, Diana Loranger, P.Geol., PhD, was hired as a field geologist by Imperial Oil in 1943, shortly after graduating with a geology degree from the University of Manitoba.

Most employers didn’t allow women to do geological field work back then. Often, the job involved long stays in remote camps, while living in tents or trailers and lugging around heavy gear.

Perhaps it was a wartime shortage of men geologists, but whatever the reason, Dr. Loranger was sent on field trips from the start.

Together with her colleagues, who were men, she collected and analyzed core samples at oil well sites around Alberta and Saskatchewan. A story in the October 1947 edition of the Imperial Oil Review, the company’s magazine, noted that “Miss Loranger has shirked none of the tasks assigned to geologists who are men, and as a member of a field geological party has walked as much as fourteen miles in a day.”

By that time, she had been promoted to a senior role and was working in Calgary, where she set up Imperial’s new micro-paleontology lab.

It was here where she developed innovative new techniques to locate oil deposits by examining microfossils to help date sedimentary rock. Much of Imperial Oil’s exploration efforts in the late 1940s—culminating in the Leduc oilfield discovery and beyond—was based on her work.

Her manager was initially skeptical about her theory that “little bugs” found in core samples could help identify fault zones, Loranger recalled many years later. “The real fun was doing something for the first time because there were no books to help you. You had to sort of scratch your head and say well now.”

Loranger earned a PhD in 1962 and worked as an oilfield consultant into the 1970s. Embracing new technology, she learned to write code in 1971 so she could computerize her paleoecology work.

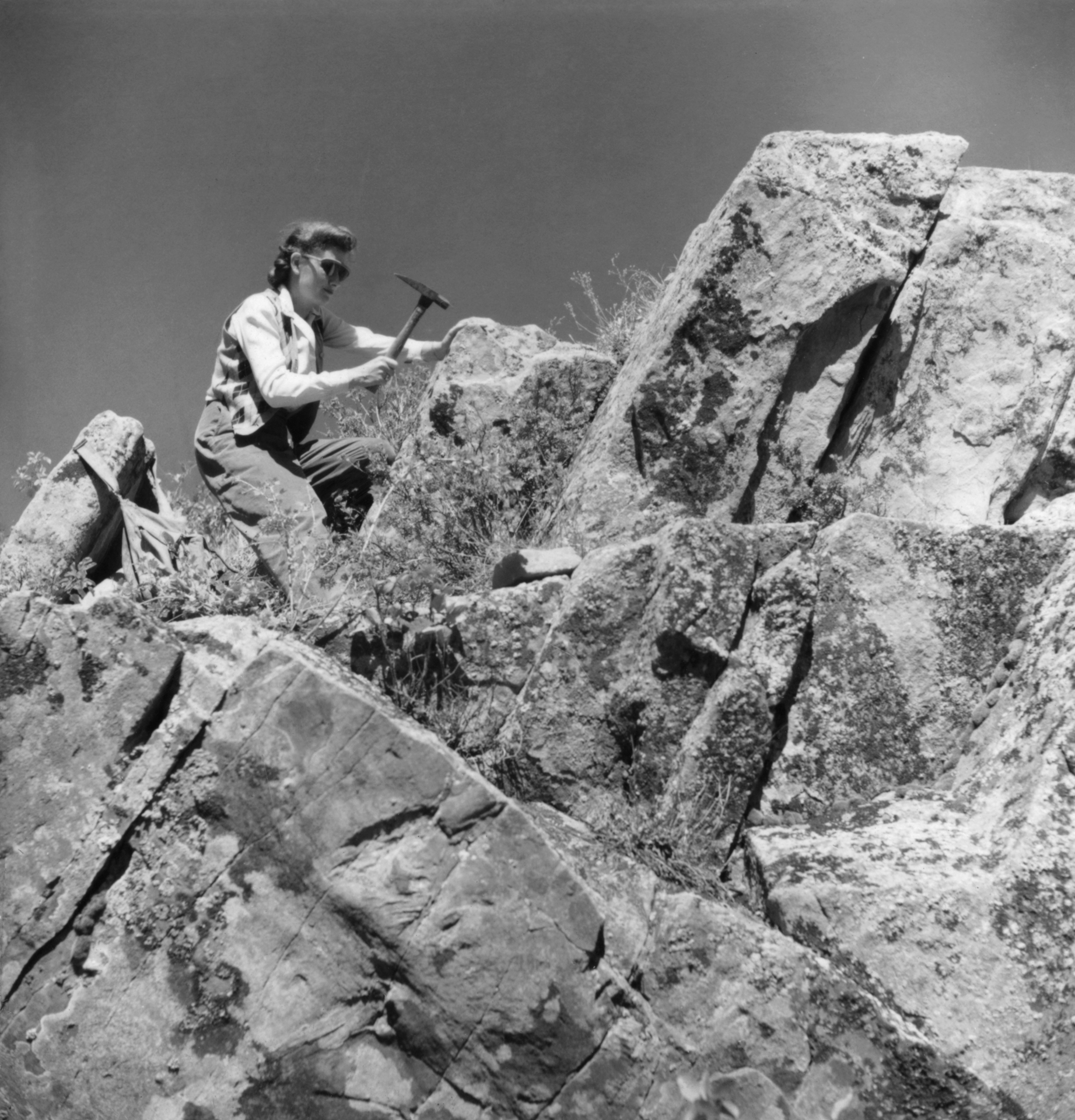

Diana Loranger uses her pick hammer to gather rock samples in the Rocky Mountains. This photo accompanied a 1947 article published in the Imperial Oil Review, which pointed out that she did the same work as her colleagues, who were men. Another story, published in the Central Press Canadian the same year, described her as attractive (twice), and noted that she was one of the few women oil geologists who had “invaded the he-man oil field of the west.”

Glenbow Archives IP-14a-1828

Ruth Reed, P.Geol.—An Eye for Detail

Further geological advances were made by Ruth Reed in the 1950s, including a hand in discovering the Waterton sour gas field near Pincher Creek in 1957.

After completing a geology degree in New Brunswick in 1951, she was working on her master’s in Toronto the next year when Shell recruited her to work at its Calgary office as an exploration geologist.

Reed became an authority on the stratigraphy—or rock layers—of Canada’s western plains and southern foothills. Her career took her across Alberta, British Columbia, Yukon, the Northwest Territories, and into the Arctic.

She’s best known for her role in the discovery of the Waterton sour gas field. Her detailed analysis of core samples from the region revealed previously missed limestone grains—a sign of oil or gas deposits.

Other geologists were dismissive, but Shell started a new drilling program based on her findings. The success of the Waterton gas field led to other discoveries in the area and the construction of the Waterton Gas Plant in 1962.

For more than three decades, Reed practised geoscience in Alberta’s oil and gas industry. She also served the association’s professions as an APEGA committee volunteer.

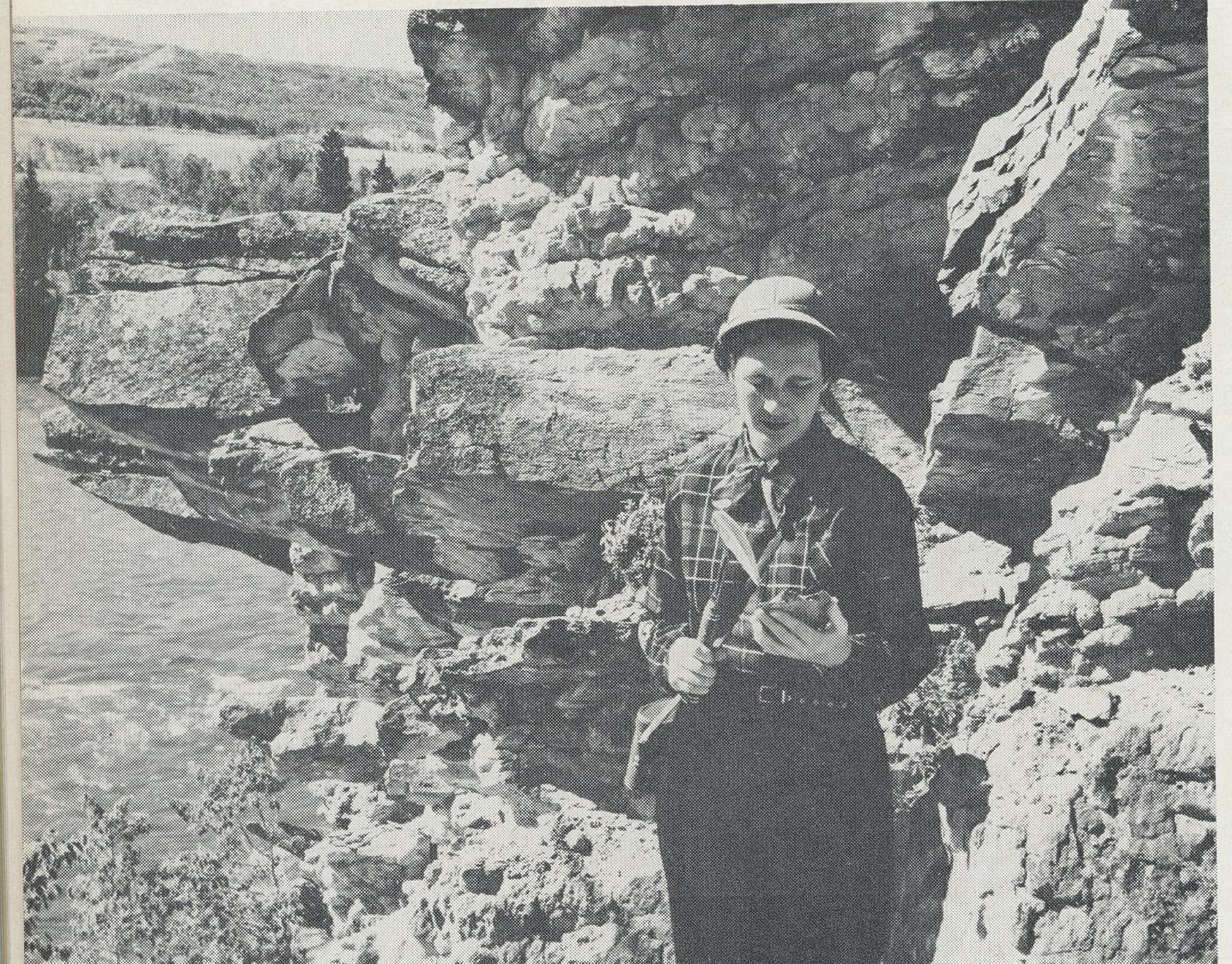

Photo courtesy of Shell Historical Heritage & Archive, The Hague, Shell News Canada April 1958

Dr. Helen Belyea, OC, P.Geol.—Exceptional in Many Ways

Women geologists with the Geological Survey of Canada were barred from field work until 1970. But Helen Belyea, OC, P.Geol., PhD, is a notable exception.

In 1950, the survey opened a field office in Calgary. Dr. Belyea and a co-worker, who was a man, were sent west to help monitor new oilfield discoveries.

She became the first woman employed by the survey to work in the field alongside men, gathering samples, studying rocks, and mapping the Earth’s surface and sub-surface, “from the tops of mountains to the bottoms of oil wells.”

Originally from New Brunswick, Belyea received a bachelor’s degree and a master’s degree in geology in Nova Scotia, following it up with a PhD in Illinois. During her 40-year career, she wrote more than 30 scientific papers and became internationally recognized for her knowledge of Western Canada’s Devonian reef system and its relation to nearby sedimentary basins.

In 1976, she was named an officer of the Order of Canada.

Digby McLaren, a friend of Belyea’s and a past director of the Geological Survey of Canada, offered this tribute after her death:

“Helen Belyea began to work in Alberta when the petroleum industry was a man’s world. But this small, determined woman, with a daunting intellect, who never suffered fools gladly, was quickly accepted as a valued colleague, as well as being admired and loved as a warm, humourous, and generous friend.”

Helen Belyea, second from right, with her colleagues near Hummingbird Reef, west of Rocky Mountain House, in 1955. Also pictured is Imperial Oil librarian Pat Thornton (left), Bill Kaufman, student geologist (second from left), and Blake Brady, with the Geological Survey of Canada. They were conducting Mississippian and Devonian stratigraphic studies in the area.

Glenbow Archives PA-2166-130