Photo courtesy of AlbertaSat

AlbertaSat Launches the Province into Modern-Day Space Race

Designing, building, and launching a satellite into space. Tracking its orbit around the Earth as it collects and sends data from above the atmosphere. And securing the space agency funding to do it again.

If you’re looking for the newest leader in space science and technology, it may be closer to home than you realize. Thanks to the University of Alberta’s AlbertaSat team, Edmonton houses one of the most exciting university space programs in Canada.

From humble beginnings

AlbertaSat—a student group with faculty advisors from the University of Alberta’s faculties of engineering and science—formed in 2010 with the intention of entering the Canadian Satellite Design Challenge. Though it didn’t win, the team quickly garnered an international reputation.

Around the same time, AlbertaSat entered the Mission Idea Contest in Nagoya, Japan, where it would win an award for the best application of nano-satellite technology to environmental issues.

As its momentum grew, the AlbertaSat team devised a new dream—to show the world that space exploration and discovery were no longer solely the realm of big organizations, and that Alberta could be a leader in the new space race.

Alberta’s first foray into space

The biggest turning point in the team’s 10-year history was the successful design, development, test, launch, and operation of its Experimental Albertan #1 cube satellite, says Callie Lissinna, the team’s current project manager.

Designed to study space weather, the satellite—affectionately referred to as Ex-Alta 1—was one of around 50 built by post-secondary institutions as part of an international initiative funded by the European Commission. Catching a ride on a rocket, it was grabbed by the Canadarm and deployed from the International Space Station.

“Out of the 50 satellites planned, 30 made it to orbit, and fewer than 10 actually worked and communicated or measured anything” recalls professional engineer Carlos Lange, PhD, one of the team’s faculty advisers and co-director of the University of Alberta Institute for Space Science, Exploration and Technology. Ex-Alta 1 was the only one created by an undergraduate student team.

“Not only was it the first made-in-Alberta satellite, but it set so many records and set a new direction for space research inside our university. It put the U of A on the map of space research in a way we weren’t before,” he beams.

Professor Ian Mann, lead faculty advisor for Ex-Alta 1 in the Faculty of Science, added, “These successes also represent an opportunity for diversification into the rapidly growing NewSpace sector of the aerospace economy here in Alberta and which we are actively pursuing here at the University of Alberta.”

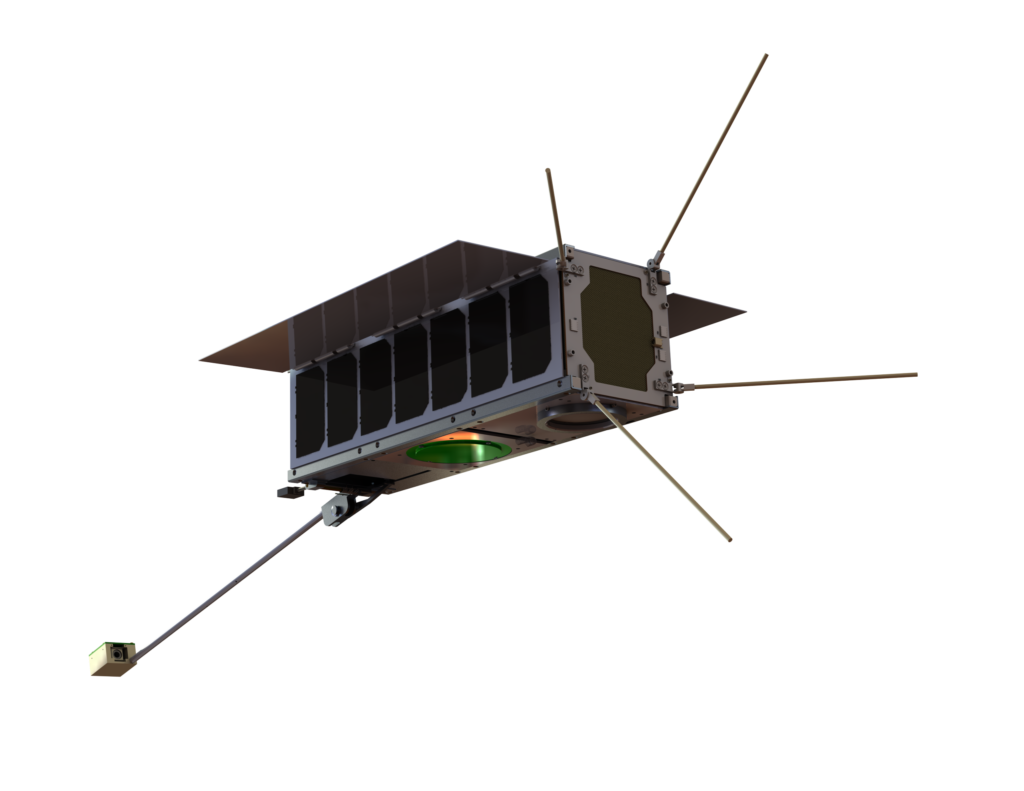

A computer rendering of roughly what the complete Ex-Alta 2 satellite will look like when it’s launched in 2022.

Photo courtesy of AlbertaSat

The second time around

Supported by funding from the Canadian Space Agency, AlbertaSat is set to launch Ex-Alta 2 in early 2022. Once the satellite starts orbiting the Earth, it will spend a year monitoring wildfire conditions and activity in Alberta, collecting data that will be used to predict where wildfires might start. It will also capture wildfire after-effects and recovery rates.

Not allowing the current pandemic to interfere with the mission, team members are creating satellite parts in at-home labs all over the province.

“We have the first version of our flight computer being built in one of our student’s garages, which we never imagined would happen,” says Lissinna. “It’s been its own separate narrative about how we’re still meeting our launch deadline—the rocket is leaving the pad in early 2022, no matter what—while working from home and without access to our lab.”

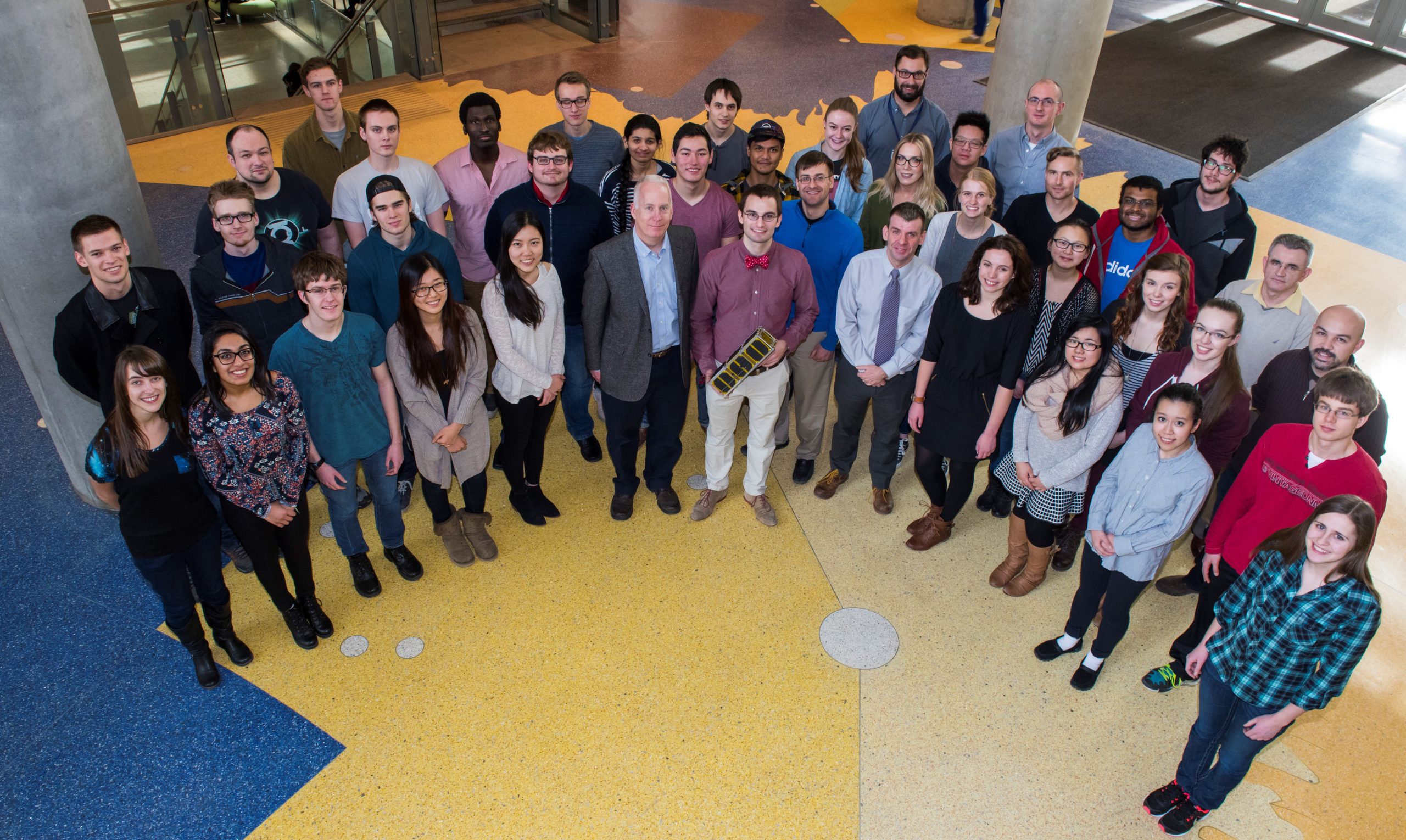

The AlbertaSat team proudly displays Ex-Alta 1, ready to be sent into orbit as part of an international initiative by the European Commission.

Photo courtesy of AlbertaSat

From class to a career

Looking for a way to get into the space industry, engineer-in-training Tyler Hrynyk spent five years with AlbertaSat while enrolled in mechanical engineering at the university. Gaining experience as a satellite operator and a project manager, his involvement with the team would prove to be serendipitous.

As he neared graduation, Hrynyk started looking for a career with a satellite company. When he heard the Dutch company that manufactured Ex-Alta 1’s metal frame—Innovative Solutions in Space— was hiring, he applied for a job.

“They recognized me from my work on the AlbertaSat team, and that gave me some credibility. I did some interviews and they knew my skill set, and it became a perfect fit.”

Hrynyk moved to Delft, in the Netherlands, at the end of July 2018 and worked as a project manager for the company for a year and a half, doing much of the same work he did with AlbertaSat.

After returning to Canada, he was hired by the Canadian Space Agency, where he will spend two years rotating through the agency’s different sectors before settling in as a satellite operator.

“My time with the AlbertaSat team gave me a lot of advantages—I was able to offer a practical perspective, and I got to design, test, and launch a satellite. Lots of new hires aren’t able to do that,” he says. “I could say, ‘I’ve seen this, and this is how we fix it.’ Having the previous experience prepared me for all sorts of situations.”

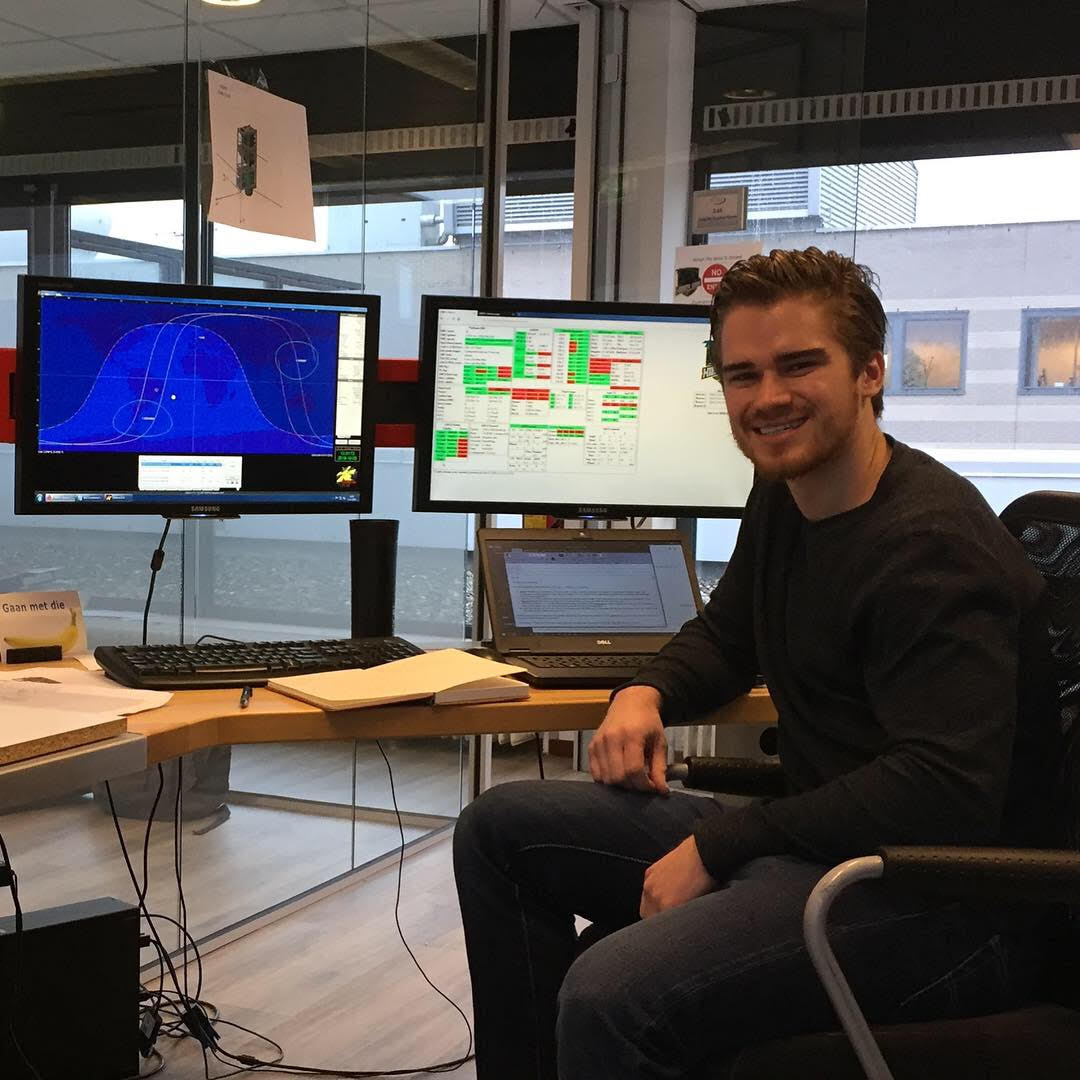

Tyler Hrynyk, E.I.T., during his time with Innovative Solutions in Space. Here, he sits in the mission operations centre, where satellite operations were conducted.

Photo courtesy of AlbertaSat

Tyler Hrynyk, E.I.T., stands in the clean room at Innovative Solutions in Space, where satellites are integrated just before launch.

Photo courtesy of AlbertaSat

Goodbye, old friend

On the night Ex-Alta 1 burned up in the atmosphere, Lissinna was at her computer, operating the satellite through what would become its last few passes overhead. She was sending it hello messages well into the middle of the night, waiting for a response to determine whether it was still operational.

After an extended period of radio silence, “I reached a point where I had to decide it was probably gone. I just sat there trying for a few extra hours before making the decision not to contact it again,” she remembers. “It was bittersweet. Operating a satellite five times a day is a bit of a marathon—it’s kind of a like a baby you need to look after all the time. It was a hefty commitment.”

After saying her final goodbye, Lissinna’s next mission was vital.

“I got a little bit of extra sleep.”

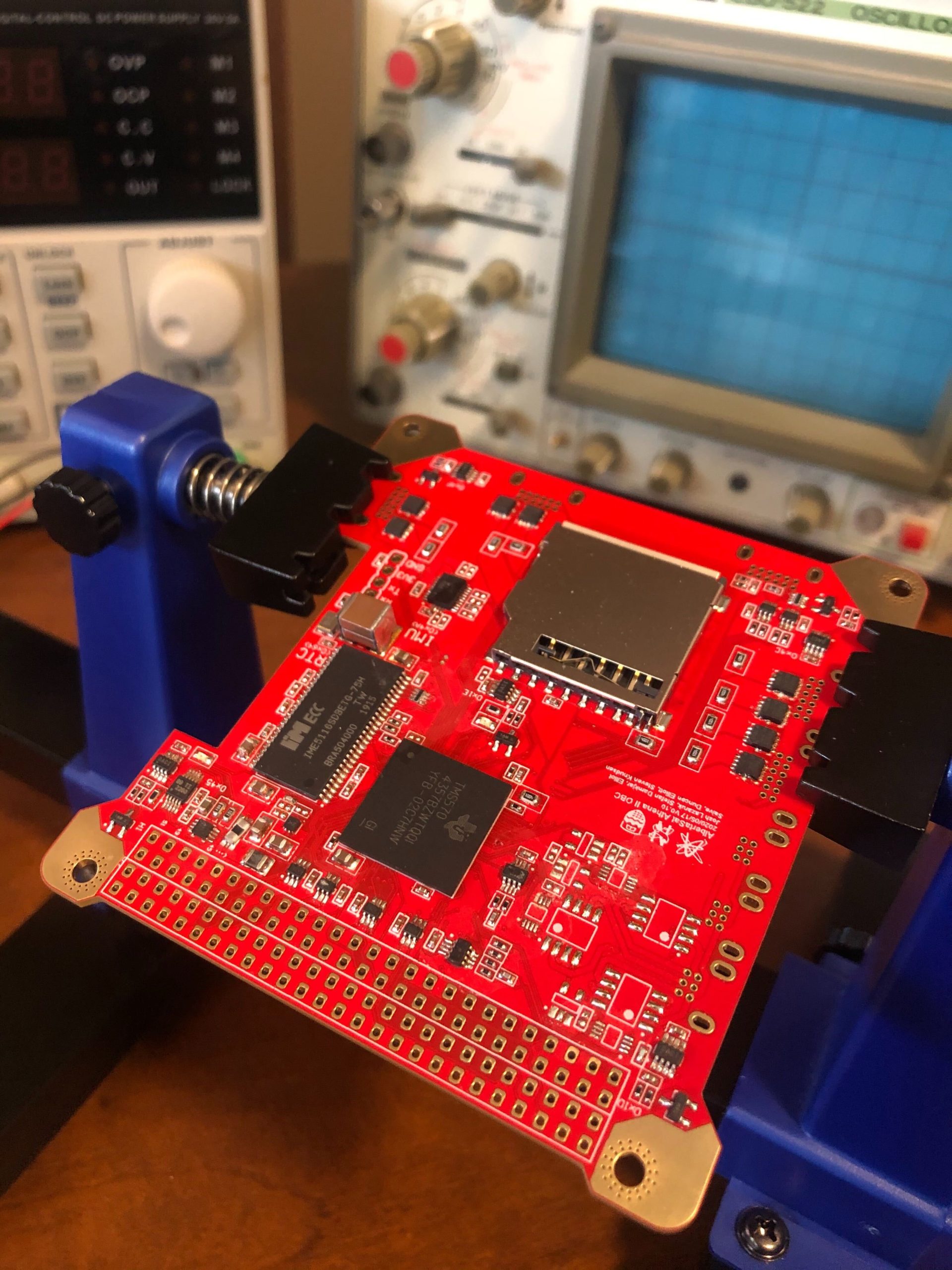

The first prototype of the main computer on the upcoming Ex-Alta 2 satellite, created by lead systems engineer—and third-year engineering student—Josh Lazaruk. Because of the pandemic, he had to do its fabrication and testing in his home this summer.

Photo courtesy of AlbertaSat

A team of undergraduate students and their professors at the University of Alberta challenged themselves to design, build, and fly Alberta's first satellite. In 2017, they made that dream a reality. Video courtesy of the University of Alberta’s Faculty of Science and Jeff Allen Productions